Episode THREE! Conversation with Shannon Hale

NOW AVAILABLE TO SUBSCRIBE ON ITUNES

Welcome to episode three of our kidlitwomen* podcast! Every week this podcast will feature an essay about an issue in the children's literature community (Monday) and a discussion about the essay (Wednesday).

In this episode, Shannon Hale discusses her essay "We're Ready" (which can be heard HERE) with Grace Lin. We hear more about Shannon's experience with gender bias with her books and school visits and how these biases affect all of us.

Read all the kidlitwomen* essays shared in March

Subscribe to the kidlitwomen* podcast on ITunes

On today's podcast you will hear:

Shannon Hale is the New York Times best-selling author of over twenty-five children's and young adult novels, including a popular Ever After High series, graphic novel memoir Real Friends, and multiple award winners The Goose Girl, Book of a Thousand Days, and Newbery Honor recipient Princess Academy. She also penned three books for adults, beginning with Austenland, which is now a major motion picture starring Keri Russell. With her husband Dean Hale she co-wrote Eisner-nominated graphic novel Rapunzel's Revenge, illustrated chapter book series The Princess in Black, and two novels about Marvel's unbeatable super hero, Squirrel Girl. They live with their four children near Salt Lake City, Utah. Follow Shannon on twitter at @haleshannon.

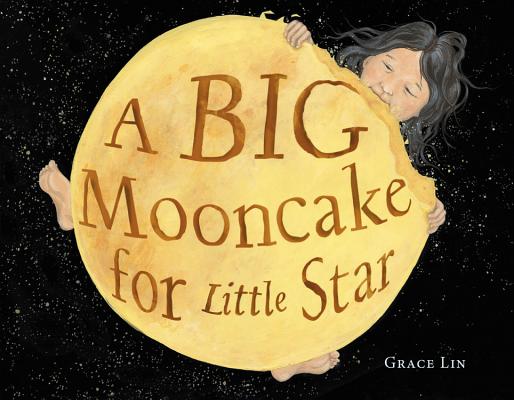

Grace Lin, a NY Times bestselling author/ illustrator, won the Newbery Honor for Where the Mountain Meets the Moon and the Theodor Geisel Honor for Ling and Ting: Not Exactly the Same. Her most recent novel When the Sea Turned to Silver was a National Book Award Finalist. Grace is an occasional commentator for New England Public Radio and video essayist for PBS NewsHour, as well as the speaker of the popular TEDx talk, The Windows and Mirrors of Your Child’s Bookshelf. Grace's new picture book, A Big Mooncake for Little Star comes out in August 2018.

TRANSCRIPT

Grace Lin: Hello, this is Grace Lin, the author and illustrator of When the Sea Turned to Silver, and I'm here talking to Shannon Hale. Hi Shannon.

Shannon Hale: Hello, Grace.

Grace Lin: Thanks so much for taking some time to talk to me today. I'm really happy to talk to you because your essay was so awesome. It was our kick-off essay for KidLitWomen*. Did it ever have a title? I think we just put it under "Kick-Off Essay." Did you have a title for it?

Shannon Hale: I think I called it, "We're Ready."

Grace Lin: "We're Ready." It was a perfect kick-off essay for our KidLitWomen* month mainly because it talks so much about how there really shouldn't be a differentiation between boy books and girl books. You talked a lot about that, about how you were presenting to an assembly of kids ... Your Princess Academy book ... and all the boys there seemed very, very not excited about the Princess Academy book. Can you tell us a little about that?

Shannon Hale: Sure. Yeah. Well, I've done ... I mean, who counts ... hundreds of assemblies in which I've talked about the Princess Academy books and the Princess in Black books and other books like that that have words like "princess" in them. I get the same reaction every time from the boys. I frequently am "boo-ed" by boys. For example, when I show my slide that shows my Ever After High books, the boys will boo.

This is something that I used to take for granted, and the teachers never stopped them. It was boys will be boys, and I began to just realize what is it saying to the girls in the audience that I just let them boo me and boo books that the girls might be interested in. So, I just started calling them on that.

I think I've experienced and seen a lot more sexism in the industry than some simply because my first big book ... and I'm always called the author of Princess Academy, wherever I go ... sounds so gendered and "girly" that I get treated a certain way in half my whole career. It took me years to start to really step back and analyze this and say this is not okay.

In the essay, I talked about one particular assembly where the school, it was a third through eighth grade, didn't allow the middle school boys to come. This has happened to me a couple of other times before. It doesn't happen every time by any means but when it happens, and I never want to make it about the particular school, it's just another sign of how we say that what women have to say should only matter to girls, and what men have to say ... because I did ask when a man came ... "Did you invite everybody?" And they did. When men speak, they have universally important stories. They speak to everybody.

Grace Lin: Let's talk about that word, "girly" for a little bit. I know in your essay, you talk about a boy named Logan who said the word "girly" in such a manner that it really took you by surprise. Why don't you talk a little about that?

Shannon Hale: Yeah. It really did. You think you've heard it all, but he was so little. He was a third grader, and he was even little for a third grader. The way he said it, he was right there in the front row right in front of me, and he said "because it's girly." I remember literally taking a step back and feeling my heart pound. That feeling that you get when you meet someone who hates you, who just hates you for some reason.

Grace Lin: Yeah.

Shannon Hale: It did take me aback, and it made me so sad it threw me for a couple of seconds. I used to be in theater, and when I do an assembly I like to have a tight performance, you know. I do not want any lulls in the energy or you start to lose the kids. It shook me enough that I was standing back there for a few seconds to grab my breath.

That word "girly," it's used as a derogative, right? It's used as a negative, which I think is interesting. There's no "boyly" word, right? "Manly" is a positive word, and "girly" is a negative word.

This is a really fundamental idea that we, as humans, whenever we have binary opposites we tend to move them into a hierarchy. So, girl versus boy. We can't just let them be side by side, we have to say which one is superior. What is masculine, we assume is superior. What is feminine is inferior, and that's what we're seeing with "girly." Things that have to do with girls are shameful and to be mocked, and this boy knew this. This boy had been raised in a world where he was fully aware of it. It broke my heart.

Grace Lin: What do you think about recently there's been a couple of articles in the New York Times about how we say girls can read boy books, girls can take on masculine traits, they can be tomboys, but boys ... there's not really a tomgirl for a boy. Boys are not allowed to be girly, like we said. Do you think that's a problem with feminism? How instead of elevating women's issues in our place, we've just kind of embraced masculine ideals?

Shannon Hale: I do. I think that has been one thrust of feminism for a long time. I don't think that everyone thinks that way, but I do think there's a branch of feminism that has said, "Women don't have power. Men have power, so in order for women to have power, we must be like men."

I remember when I was in the sixth grade, my mother who is very conservative, very. She was against the ERA. I was supposed to be a lawyer in this mock trial at school. I went to my dad's closet to borrow a blazer and tie, and she said, "I guess I'm just feminist enough to think that a woman doesn't have to dress up like a man in order to be powerful."

Grace Lin: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Shannon Hale: It was so unlike anything she had said to me or anybody had said to me in my very conservative community, that it stuck with me for years. I've thought about that a lot. It's affected my writing. When I started writing, my first book was a fantasy novel, and I was tempted to have this girl who started out in a weak and submissive role to learn to sword play, and ride a horse, and go to battle, and fight people like a man would.

Grace Lin: Yes.

Shannon Hale: And I loved those kinds of books. There's nothing wrong with them, but I was so aware of that I decided the kind of stories I want to tell are the way women can be powerful without having to take on a traditional male role.

Grace Lin: Yeah. I think -

Shannon Hale: I think -

Go ahead.

Grace Lin: No. I think that's what is so challenging these days in our writing and in the world.

Shannon Hale: And I think, for me, what feminism says is you have a choice. You can be whatever you want. It doesn't say you have to be what we consider to be masculine, and it doesn't say being feminine is bad. It's saying you get to choose.

In the past, society chose for us, right, and told us "Women, these are your roles. Men these are your roles. There's no fudging the lines." Now, what feminism is trying to say is, "You can choose. All the options are open to you. If you want to be a stay-at-home mom and wear skirts all day and talk in a high, squeaky voice, you go for it." I believe that passionately. That should be the choice.

Those should be your choices, but it really takes effort because these are ideologies, right, that are invisible to us. We don't even notice. They feel natural to us, and it really takes effort for us to step back and go, "Okay, the way I'm saying 'girly' and the way I'm judging these things is a problem. I can choose to look at this differently."

Grace Lin: You were saying about choice. In your essay, you emphasize reading and sharing these books is not "either/or," that it's "and." It's not boy or girl. We're not celebrating boys or girls. We're celebrating both, or non-binary, sorry.

Do you find that you have to always emphasize that, that's it's an "and" not an "either/or"? Do you think that's something that we need to constantly re-say?

Shannon Hale: It is. It's a theme I found coming through in my books a lot because if I put it in story, will it come across better? It is something I feel like I have to say all the time. Every time, for example, I'm interviewed about Princess in Black, which is our early chapter books series with LeUyen Pham and my husband, Dean. It's about this princess who dresses in fluffy pink dresses and wears glass slippers. When monsters invade, she puts on the mask and cape, and she goes and fights monsters. I'm constantly hearing people say that, "The superhero side of her is the better side. Aren't we glad that she gets to do that?"

I'm constantly having to reiterate, "She gets to do both! She wants to do both! She likes the tea parties. She likes the fancy dresses. Why can't she do both?" Not just for girls, but for boys too. What I think is important, because you mentioned non-binary kids too, is when we hear people say this is a book for girls or this is a book for boys, they're talking about one kind of kid. They're saying there's only one kind of kid that likes this and that's a girl and all girls are the same, and there's only one kind of boy.

As a parent and as a person that lives in the world, I know that's not true. It's just not true at all. There are all kinds of boys and all kinds of girls and all kinds of kids that don't identify as boy or girl. They all deserve stories. They deserve stories that are about people who are like them and people who are different. When we think about it that way, it's so logical and yet this is so deeply ingrained that I can tell you every time I speak about this, I have dozens of people come up to me afterwards and say, "I never thought about it before."

Grace Lin: Oh, so interesting. Well, that actually ties into this question. You know, you said in your essay that you've been talking about this for decades and then all of a sudden, I think it was in 2016 when you said it was on your third Princess Academy tour, that people starting caring. You wrote about it in Twitter, and all of a sudden you started getting all this attention for it. Why do you think people suddenly started to care?

Shannon Hale: I don't know. I honestly don't. I was shocked. When it happened, this school with Logan and with the boys not being invited, I didn't even Tweet about it immediately because it was like, "Yeah, it's par for the course. This happens when you're the author of Princess Academy." It wasn't even until a few days later that someone said something on Twitter that reminded me of it, so I just Tweeted it randomly. It was like, "Yeah, I was at a school last week, and this happened." So many people were outraged and wanted to know the school, which I would not reveal because I didn't want to make it about them. They weren't trying to be bad. They weren't trying to hurt anybody, they're stuck in the same unconscious biases that we all are.

I was really shocked so I wrote an essay about it, explaining more what happened and, again, I was shocked that it was viewed and read tens of thousands of times. It was such a dramatic difference from where I feel I've been kind of yelling into the void for years.

I don't know why now, but I'm encouraged. Why is the "Me Too" movement now? I mean, many of us have been talking about sexual harassment for just as long, and nobody seemed to care or feel like sexual harassment was a problem. Now, suddenly, people are listening. Is it just the right time? Is it social media?

Grace Lin: Is it the election, social media, all those things? I felt the same way about diversity, too. I feel like I've been talking about diversity for a long time, and then all of a sudden in the last year, couple of years, it just blew up, which has been great but also took me by surprise.

Shannon Hale: Yeah. I'm the same way. I started to feel like am I crazy? Have I not been talking about it? So I started going back and looking at old blog posts from 12, 10, 8 years ago, and I've written lots of blog posts about these issues and gendered reading and lots of blog posts about representation in fiction and race and disability. Reading the comments is interesting because so many people are like, "What are you talking about? A book is just a book. You don't need to think about those things."

I'm like, "I'm not crazy. I was talking about these things." I think that was the culture, right, that many of us were thinking and talking about these things, but individually. Now, we have this momentum and I think part of it is Twitter and Facebook and ways where we can all talk as a group, rather than sort of shouting into our individual blogs. That's what has helped gained the momentum.

Grace Lin: Yeah. I mean, that's part of the whole KidLitWomen* agenda was to take these conversations out from behind closed doors and get it out there. That's great, so maybe hopefully we're part of that change.

Do you have any advice on how all of us, or we, could advocate the change?

Shannon Hale: I do have so many ideas. Just the basics: when there are boys in your life and they want a book recommendation, offer them three books and make sure at least one is written by a woman and is about a girl. It's just that simple. Sometimes when I talk about these things, I get reactions of like ... I don't know why we always think in such extremes.

They're like, "So now you're saying boys can't read books about boys anymore."

I'm like, "No. What? Nobody is saying this."

It can be as simple as just offering. When you offer without shaming them, without a caveat saying, "Even though it's about a girl, you'll like it." You're just saying this is an okay thing. You have permission, and that's huge.

When you have a boy in your life that you buy a book for, buy him a book about a girl occasionally, especially a book written by a woman about a girl.

Grace Lin: I would add a person of color, too. I think that would be really interesting. Not so much interesting, but I think that's imperative, too.

Shannon Hale: Absolutely. For white kids, they should have bookshelves full of books written by people of color.

Grace Lin: With characters of color, too.

Shannon Hale: Yes. Characters like themselves, and characters different from themselves, in everyway ... LGBTQ kids, kids with disabilities that these kids don't have or different ones than they have. This is the world that we live in. The way we say books about girls are not for boys, we've been doing the same thing with race, and every other kind of main character ... pre-selecting and almost like protecting kids from having to think about anyone different from themselves, which flies in the face of what literature and stories are even for.

Grace Lin: What I think is interesting, and I'll put in my own little experience is that recently my book, The Year of the Dog, we just changed its cover. Before it was just a plain little drawing of a dog on the cover, and now we've changed it to an Asian girl on the cover of the book. It's a photograph, and I think it's adorable.

I was having this conversation with a school who had just done a one-book, one-read of Where the Mountain Meets the Moon, and they said, "Oh, we had this great idea that we would follow up next year with another one-book, one-read with The Year of the Dog since we just read Where the Mountain Meets the Moon."

The teacher kind of said, "But, then we saw the new cover with the girl on it, and we don't think the boys will read it."

Shannon Hale: Yeah.

Grace Lin: I just thought that was so heartbreaking.

Shannon Hale: Yeah.

Grace Lin: It's the same exact book, yet just because now the cover, the packaging, has a photo of a girl on it, it changed everything.

Shannon Hale: What's sad is that it's the adults that make that true. So, I have found in my experience when I go and do signings, for example, the majority of the people there are women and their daughters. Quite often, there will be one boy there, a teenage boy, and he'll have a stack of my books and he doesn't seem to be ashamed to be there. There was no consciousness of, "Even though I'm a boy, I like your books." He just was happy and enjoyed my books and wanted me to sign them.

Whenever I meet a boy like that, I would start talking to him and try to figure out, "What's different about you? How did you escape this?" Most of the time, what I've found is they're home schooled.

Grace Lin: Oh, how interesting.

Shannon Hale: There's something that happens ... there's someway that we're socializing kids in the environment in school. It is teachers like that teacher who made those assumptions and librarians who make those assumptions, but even more so it's the peers who are constantly policing each other to make sure that nobody is crossing any lines. They're trying to figure out what it means to be a boy and a girl, and so what they learn is what it means to be a boy is to be not a girl. So, all the peers are constantly watching for any sign that a boy is anything like a girl, then they make fun of him for it.

It doesn't happen in the home school environment. They are not, for the most part, raised with those same expectations and feelings.

It's also a cultural thing. I'm talking to a man from South America, and he was like "I go to a signing of Isabel Allende, and the crowd is full of men and women." I went to a signing of her in Utah when she came, and he was the only man there. So there is something in our culture we've decided that this is natural and true, but it's not. It's just perpetuated by people who think it's true, and so make it true.

Grace Lin: Have you seen any changes since you've written this essay, or the one that you wrote in 2016?

Shannon Hale: At times, I despair because ... and I'm sure you've felt this way too ... when you feel passionately about something and you see how slowly change comes and how often people don't get it or care when I care so deeply because it's about so much more than just books. It's about these human beings and how they're set up to interact with other human beings for the rest of their lives.

Grace Lin: Yeah.

Shannon Hale: It has huge consequences, these beliefs that men shouldn't care about or emphasize with girls ... huge consequences, real life consequences, life and death consequences in some cases. It is discouraging to see how slowly and how stubbornly some people resist this. I have seen change, enough that it gives me hope.

It really means a lot when I meet people who will come up to me and say, "I heard you talk about this four years ago, and now I've decided to become a librarian so that I can help the kids find books I write for them without shaming them" or "I completely change the way I buy books for my kids now."

This one librarian, wonderful, such a great idea ... I think her name was Margaret Millward, and every year now she does a challenge with I think it's the fifth graders. She challenges them all to pick out a book that is clearly about someone of the opposite gender. She challenges all the boys to pick out a book that's clearly about girls or what they consider to be for girls. Same for the girls to read about boys, and because it's a challenge it's like she's giving them permission, it's okay. They read the books. They actually take them home and read them. She said the best thing that came out of it was that the kids were talking to each other about the books, and the boys and girls were talking where they were recommending, "You'd like this. I think you should read this next." There were, I think, three boys the first time she did it that their parents forbade them from reading the book.

Grace Lin: Oh, how sad.

Shannon Hale: She wrote notes and sent them to the parents, explaining what they were doing, asked them to reconsider, and the boys came back and said they're forbidden. They cannot read a girly book. So, we know there's still a long way to go. Sometimes gendered reading happens because we're not thinking about it, but sometimes it's very deliberate. There's very much an idea that girls are lesser than boys, and by exposing boys to girl stories that we are going to diminish them somehow.

Grace Lin: That goes for diversity reading, too, and I don't understand that but I know that's how people feel. That's very discouraging sometimes when you're faced with that.

Shannon Hale: It's interesting that everybody seems to understand these things intrinsically, but can't vocalize them. You hear a lot of white people say, "Where is my privilege? I don't know what you're talking about ... about white privilege." Yet, they understand that equal rights somehow is going to diminish they're power. They understand that letting their kids read books about people of color are going to develop empathy for those people and then they won't keep themselves in a separate upper sphere or however they're conceiving of it. They understand on one level, and yet not on a second.

Somehow, we have to get those unconscious understandings and conscious together.

Grace Lin: Well, it's almost like these myths that they believe. Personally, I don't believe that is true ... If they can emphasize with other cultures, that will diminish theirs, but I know that's how they see it.

Shannon Hale: Yeah. I don't get it either. I grew up in a very homogenous neighborhood that was almost entirely white. Then, I went to high school, and it was very racially diverse. I think the most racially-diverse high school in Utah. Suddenly, in some classes I was a minority. I loved it. I just ate it up. I felt like I could finally breathe. It was so wonderful, and yet all of my friends from my neighborhood transferred out of the school, and some said because they were uncomfortable with the people of different races.

It was one of those realizations where I was like, "Okay, we're not all seeing this situation the same way." It felt very natural to me, but it felt unnatural to them to be integrated in a more diverse society. It's something we have to consciously be talking about.

White people, what we don't understand is, we have been raised in a culture that caters to people who look like us, who put people in power who look like us. That has an effect from a very young age. We watch movies and we read stories through the eyes of white people, and white authors, and white filmmakers. We've only seen one perspective, but people of color have been forced to be raised in this dominant culture and are seeing movies and reading books through the eyes of white people, yet they're also living their experience. So, people of color are like way ahead of white people in terms of understanding, and flexibility, and social intelligence.

For writers, especially, if we're white, it just takes more work to understand and put ourselves in different characters' point of view from the very beginning. Same way if you only were raised with speaking one language, it takes a lot more work to learn a second than it would if you were raised with it. Men, it takes a lot more work to write female characters because, in the same way girls are raised learning boys' stories in books and in movies and seen through the eyes of men and seeing themselves through the eyes of men all their lives, we understand men and ourselves, and we're more flexible and it's easier for us to write male characters, as well as female. For men, it's harder and they have to work harder.

Male writers need to be reading a lot of books written by women. I have met many male writers who have never read a book written by a woman. I can't imagine being a woman and never having read a book by a man. I mean, you couldn't get through high school.

Grace Lin: Exactly.

Shannon Hale: But that's the reality that is sort of invisible is that men don't feel like they're dominating anymore, but still everything is still catered to them and through their eyes.

Grace Lin: Well, thank you so much Shannon. I don't want to take any more of your time. This has been a great and fascinating conversation. I just want to finish up with the two questions that I'll be asking all of our guests.

The first question is: What are you working on now or what's your new book coming out?

Shannon Hale: Most recent book was a book my husband and I wrote for Marvel about Squirrel Girl. She's an actual Marvel Superhero. In the comics, she is in college, but we put her in middle school because when you're a girl with a five-foot squirrel tail, there's no better place to be than middle school. She has the proportional strength, speed, and agility of a squirrel, which turns out to be incredibly powerful. She has the powers of squirrel, but she also has the powers of girl.

Grace Lin: Cool. All right. My last question is: What is your biggest publishing dream. Now, I'm telling all my guests that when I ask this question, I want them to dream huge, big, like a dream that they're almost to embarrassed to say out loud, and I don't want to hear them say, "I just want kids to love my books. I just want to make a living." We're passed that. I want like the biggest, most embarrassing ambition you can think of.

What is your publishing dream, Shannon Hale?

Shannon Hale: Grace, I love that you're doing this because it is ... Is it a woman thing that we have to be like, "Oh, no, no. I don't know. I don't want to be greedy." We're taught that ambition is bad, right?

Grace Lin: Exactly.

Shannon Hale: Women are taught that. I am ambitious, and it took me years to realize that I am very ambitious.

Grace Lin: And we don't have to be ashamed of that.

Shannon Hale: No.

Grace Lin: That's what I feel.

Shannon Hale: You know, there's so many little milestones that I would love to -

I would love to reach number 1 on the New York Times Bestseller List someday.

I would love to make more movies. I recently wrote a screenplay for Princess Academy. I would love to see that made. I'd like to be a producer on that, and say "Yes. No. Yes. No" like that.

I would love -

I don't know. I want it all. I want the world.

Grace Lin: I think you deserve it. Well, thank you so much, Shannon.

Shannon Hale: Thank you, Grace.

Grace Lin: Thanks so much for listening to the KidLitWomen* podcast. Even though I do sort of shamelessly mention a title of one of my books in the introduction sometimes, I'm actually offering this podcast for free in the hopes that it helps improve the children's literature community. With that in mind, I hope you'll help support it too.

In the spirit of equity, we will publish transcripts of our conversations at the website www.KidLitWomen.com. Unfortunately, this service is a little costly, so I'm asking for donations to support this endeavor. At our website, www.KidLitWomen.com, at the bottom of every page you'll see a button that says "Donate for Transcripts," which will lead you to our PayPal account.

Please consider donating. Any amount will be helpful to help keep this podcast going. I'm not looking to make any money off this podcast. I'm definitely losing money, so any money given will be used to pay for transcripts. Any additional money will be used to help pay for hosting and recording costs and if, for some miraculous reason, the donations exceed the costs, I will donate the extra money to We Need Diverse Books.

Thanks so much.