Episode 54! The PW Publishing Industry Salary Survey, 2018: Conversation with Kheryn Callender, PART 1

NOW AVAILABLE TO SUBSCRIBE ON ITUNES

Welcome to episode 54 of our kidlitwomen* podcast! Usually, this podcast features an essay about an issue in the children's literature community (Monday) and a discussion about the essay (Wednesday).

This week’s episode is different. In this 2-part interview Grace Lin talks with author Kheryn Callender about the PW’s 2018 Industry Salary Survey and their experiences working as an editor in children’s publishing. This is Part 1 of the interview, please come back on Wed to hear Part 2.

This past November, Publisher’s Weekly published their “Industry Salary Survey, 2018.” It was a very revealing survey, here is an excerpt:

Change comes slowly to the publishing industry. Despite years of discussion about the need to bring more people of color into the workforce, 86% of respondents to PW’s 2017 salary and jobs survey were white, down 1 percentage point from 2016. (The annual survey was sent out to employees of publishing companies this summer, and we received 664 responses.) There was one encouraging sign in the survey regarding diversification efforts: nonwhite respondents with less than three years of experience accounted for 19% of all nonwhite respondents, whereas white respondents with the same amount of experience made up only 9% of white respondents—an indication, perhaps, that publishing is starting to attract young people of color.

Diversifying the workforce seems to be more important to people of color than it is to white industry members. Though 53% of nonwhite respondents said strides have been made in diversifying publishing’s ranks, 38% said no progress has been made, and only 9% said they don’t know whether things have improved. Among white respondents, 46% said that improvements have been made, but 31% said they don’t know how diversity was faring. In terms of improving the diversity of titles, 78% of all respondents said improvement has been made, with more white respondents (79%) seeing things in a favorable light than people of color (73%). A much higher portion of nonwhite respondents (20%) than white respondents (6%) said they feel no improvement in title diversity has been made.

Another consistent feature of publishing’s workforce revealed by our survey has been the pay gap between men and women. In 2017, the average salary for men who responded to the survey was $87,000, compared to $60,000 for women. Despite that $27,000 disparity, the gap was $1,000 smaller than in 2016. Women closed the pay gap in the management ranks—the most lucrative job type—by $3,000, and the survey indicates women have made real progress in moving into management positions. According to the survey, 59% of management jobs were held by women in 2017, up from 49% in 2016. In editorial, women who responded to the 2016 survey outearned men by $1,000, but the men who responded to the 2017 survey outearned women $77,000 to $55,000.

Women continued to account for 80% of respondents, the same percentage as in 2016. There was one change in the gender composition of the industry last year. For the first time, 1% of respondents identified as nonbinary.”

There is much more to this survey, including some eyebrow-raising quotes about sexual harassment within the industry (which we hope to address in a podcast at a later date). In response to this survey, author and previous Associate Editor at Little, Brown Books for Younger Readers, Kheryn Callender posted this tweet thread:

Wow. This makes my heart hurt. To make real, lasting change, these numbers need to change--and not only by hiring POC for entry-level positions. There needs to be a conversation around retention. What can publishing do to ensure POC are able to stay? I ended up having to leave.

<I tried> to move up as quickly as possible, but I was often slowed down because of the idea that I hadn't paid my dues. How many other POC are putting in the time and work while others are not putting in as much work, b/c they know they will get that promotion if they wait long enough?

Let's also talk about the table. I literally felt uncomfortable at the table as the only black person in the room 98% of the time. I didn't realize until I left how much of a stress this creates, to look around and feel like you physically don't belong. That added layer of psychological stress is something white colleagues don't have to deal with, but it can affect the way POC work and socialize at every level. I often felt like I was being "loud" and "obnoxious" by people with a different culture and outlook than my own. I began to shut down and not feel comfortable speaking, even for issues that are important, such as for racism/homophobia/etc. found in manuscripts.

Also, re: the table it's time to stop bringing our folding chairs to the table. Some people need to get up and make space. Are you one of the 86% of white folks and aren't 100% invested in publishing? Make room. Hiring managers, also hire POC not just at the entry-level hire POC for mid/senior positions if they have correlating experience.

And let's consider that the issue isn't only from white folks. I felt more than once the feeling of "there can only be one" from other black/brown folks in the industry. Support POC at all levels, uplift one another. Celebrate their victories. Know the names of not only the 7 black kidlit editors who managed to stay, but the newer assistants as well, and know that there's a chance they're going through hell so that they can make the change we all want to see.

Let's also undo the idea that all of publishing is evil. I felt so isolated on all sides: being the only black person in the room, and then feeling like I was an enemy by POC because I'm in publishing. There are people there who are working hard and making sacrifices to make change.

Final thought: we need to get rid of the idea that a person can't be considered viable "just because they're POC." White folks in publishing have been considered more viable for years because of their race. Even if there's someone who has a lot to learn and needs to grow give them that chance to learn and grow. I was a mess when I first started. There's a reason for that. It was my 1st job. I didn't have generations of family members who know what it means to be professional in NYC. I didn't have anyone to depend on except for one friend and one mentor, whereas others (probably same group who can wait to "pay their dues") might be able to go to a larger network to learn, and come in knowledgeable. It isn't hiring "just because they're POC"--it's actively fighting a system that's unfair.

My thoughts, my opinions, but really feeling like the industry needs to be shaken up to make real, lasting change.

This was so thought-provoking, that we invited Kheryn to the podcast to continue the conversation.

This is Part 1, please come back on Wednesday to hear Part 2.

Read all the kidlitwomen* essays shared in March

Subscribe to the kidlitwomen* podcast on ITunes

On today's podcast you will hear:

Born and raised in St. Thomas of the US Virgin Islands, Kheryn Callender is the author of Hurricane Child and This is Kind of an Epic Love Story. Kheryn was previously as Associate Editor at Little, Brown Books for Young Readers.

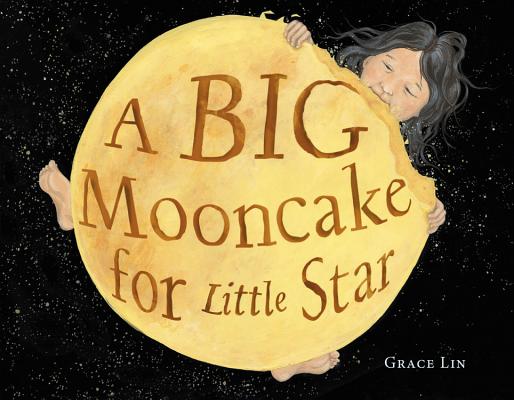

Grace Lin, a NY Times bestselling author/ illustrator, won the Newbery Honor for Where the Mountain Meets the Moon and the Theodor Geisel Honor for Ling and Ting: Not Exactly the Same. Her most recent novel When the Sea Turned to Silver was a National Book Award Finalist. Grace is an occasional commentator for New England Public Radio and video essayist for PBS NewsHour (here & here), as well as the speaker of the popular TEDx talk, The Windows and Mirrors of Your Child’s Bookshelf. Grace's new picture book, A Big Mooncake for Little Star is now available.

NOTES:

In this episode:

Grace mentions this PW article: “How I Landed in Children’s Book”

Grace and Kheryn discuss the “Suicide Bomber Sits in the Library” controversy, outlined HERE.

TRANSCRIPT

Grace: Hi Kheryn.

Kheryn: Hey Grace!

Grace: Thanks so much for coming onto the podcast. Before we start, I want to tell a little bit about our history just so people know our relationship as well as I want to do a little bit of a confession.

Grace: So, you used to be an associate editor at Little Brown Books for Young Readers which is the publisher of most of my books. When I sent in a draft of a novel, When the Sea Turned to Silver, you were one of the readers that did manuscript comments, and I remember, when I received the comments, I was so annoyed. I was like, "Oh, they're so wrong." I even complained to Alvina, my editor, who very diplomatically said, "Well, just think about it."

Grace: So, I did, and when I finally started getting into the meat of revising, all of a sudden, all of your comments made so much sense, and I realized how actually right you were, and I really have to give you a lot of credit for making the book so much better.

Kheryn: Oh thank you.

Grace: So, I wanted to apologize for cursing you behind your back, and I want you to know that that experience has made me just that much more aware of what I can learn from you.

Kheryn: Oh wow. Thank you so much.

Grace: Okay, but let's start with you. Okay, so let's start with the basic stuff. You worked in publishing for how many years? Can you tell me how you got started?

Kheryn: Yeah, I started as an intern in 2013, and then was hired as an editorial assistant in 2014, so I've been in publishing for about four and a half years before I left in August of this year.

Grace: And you left to become a full-time writer. Is that correct?

Kheryn: Well, I wanted to try different things. I want to try to see if I could get into TV and film. Right now, with my writing deadlines, it does make sense to kind of focus on the writing for as long as possible, but I do want to jump into some new things soon.

Grace: So, just for the purpose of this topic, how do you self-identify.

Kheryn: I am black. I am queer. I am trans, and I use he/him or they/them pronouns.

Grace: Okay, so in my intro, I talk about how your reaction was one of the few reactions I saw online to the PW Industry Salary Survey. Why do you think the PW Survey affected you personally?

Kheryn: I felt very personally affected by it because I had made it my mission and my life goal to diversify publishing in children's book to help children see themselves reflected since I really did not see that when I was a kid. And after needing to leave publishing, I felt like I had kind of failed in my goal, so the survey, to me, symbolized a lot of the main reasons for my failure. There's so much talk about diversifying in publishing, but not enough is really being done to see that happen successful and to keep people of color and marginalized people in the industry.

Kheryn: So, the survey kind of just hit me hard personally but also professionally, just wanting to see ... It kind of symbolized everything that still needs to be done.

Grace: So, for those who listen who might not be so familiar with children's publishing, why do you think diversifying the workplace is so important?

Kheryn: So, I'm not sure how much into the nitty-gritty I should get, but I'll give an overview.

Kheryn: I feel like ... [inaudible 00:03:31] publishing houses different departments from art and design to marking and publicity, [inaudible 00:03:39] and editorial, and each of these departments affect the book's production, so if the workplace isn't diverse, an offensive book could be bought by an editor who doesn't realize it's offensive. Sorry. You can backtrack a little bit Grace. I lost my train of thought.

Kheryn: So, if the workplace isn't diverse, I feel like an offensive book can be bought by an editor who doesn't realize it's offensive, and then a non-diverse design department might help to create a stereotypical artistic depiction on the cover or in a picture book or in a graphic novel as we've seen recently as well with the problematic book by Abrams.

Kheryn: And even for books that aren't offense, I feel like, for example, marketing and publicity might not see the importance of a book that has characters that doesn't look like the people on the marketing and publicity team does, so the book might fail giving publishing more ammunition to say, "See, diverse books don't actually work."

Kheryn: So, I think it's all connected. The less diverse publishing house or in print, the less opportunity there is to catch and stop an offensive book from being published or to promote positive diverse books.

Grace: So basically, when you don't have a diverse workplace, it really affects the books being published. You can actually, I guess, create books that are quite harmful if you don't have these kind of safeguards, meaning a diverse workplace.

Kheryn: Absolutely. Yeah.

Grace: So, you mentioned it very briefly about the Abrams book because it's something high in my head a lot because I just recently talked with [inaudible 00:05:21] about the publishing controversy of that book, a suicide bomber sits in the library, and the question everyone was asking was, "How did a book like that even get bought?" So, what are your thoughts on how some of these problematic projects still manage to be bought?

Kheryn: You know, I don't [inaudible 00:05:44]. It's okay. Go ahead.

Grace: I mean, I guess I just feel like it was one thing about ten years ago, but now I feel like everybody is so hypersensitive or at least hyper-aware or should be hyper-aware of these things, so it was just kind of flabbergasting to so many of us.

Kheryn: Yeah, I don't know what the details of that situation might be, but if I'm going to go ahead and assume that it's anything similar to what I've experienced in the past, then I'll speak to that. I've seen books like this move through the process of being bought and very nearly being bought, and each time it's a situation of well-meaning authors and editors who really just don't know any better, and I'm not going to say any names or any of the titles of the books I'm thinking of, but the one connecting thread for all of these problematic books has always been a story that is in response to race and in response to the climate that we are in now, given the administration, for example, but from the lens of a white viewer.

Kheryn: So, over the years, the easiest red flag for me whenever I think that a book is probably going to be problematic, and I should probably read it for the editorial team to see if it could either be stopped or changed early on is when the manuscript was not in own voices manuscript, and when the buying editor has nothing to do with the main character's identity in any way either.

Kheryn: So, the problem is that the ones making the decision on whether to move forward with a project like that or not are also overwhelmingly white, so they're not going to see those problematic issues, and in some cases, would even relate even more to the problematic story because it was created for the white viewer rather than for the people of color using that marginalized character.

Grace: So, what do you think about own voices just from an editorial standpoint, and then maybe as an author's standpoint. I have so many mixed feelings about it. Early on in my career, I kind of felt like, "Oh, anybody could write anything." But as time has gone on, especially as I have done more and more school visits and I see how important it is for kids to kind of see somebody who looks like them, it's become much more of an important issue to me, but I'm not sure if publishing has grown that way or not. What do you think?

Kheryn: I have very mixed feelings also. I actually started out feeling very strongly about own voices and feeling like only people of a specific identity can write what they have experienced, and of course, I feel like that is the other end of the spectrum where people should be able to relate to other identifies or feel like they have experience or have close people in their lives where they're able to write an identity that isn't necessarily just theirs.

Kheryn: And then also, even as an author, I'm black. I'm from the Caribbean. I'm trans. Does that mean that's the only identity I can ever write for the rest of my life. That's very specific. At the same time, there does definitely need to be a balance and discussion on why it is that to this day. It's so hard for specific, marginalized groups to publish their own stories and to tell their own stories and are struggling to get an agent and struggling to get the book deal that would allow them to continue to work creatively, but why it is that there are others who are not of that identity, and most usually privileged white people who can tell the stories for them, why is it that there is such an imbalance, and we keep going to the privileged people who aren't marginalized to tell these stories.

Kheryn: If we say something like, "Oh, we can't find the black author." I'm just saying black as an example. We're not able to find a black author to tell this story, I think more often than not, we're not looking hard enough, or publishing isn't look hard enough, so ultimately I do think there is an imbalance right now, and there needs to be more of a balance to find own voices stories.

Grace: Yeah. That's the thing that I have such mixed feelings about, own voices. You kind of nailed in on the head. Own voices, there's some things about it that I feel very strongly about, but I also don't want it to be limiting to people of color. Does that mean that I can only do Asian books, which I do, but it's nice to know that I wouldn't have to, that it's just a choice.

Grace: I guess, also, it was one of the things that a lot of people were complaining about with the suicide bomber sits in the library is that so many Arab American aspiring children's book authors complained about how hard it is for them to break in, and then, there was this book that was definitely not an own voices book that was so problematic.

Grace: That's why it's a very tough balance.

Kheryn: Mm-hmm (affirmative) absolutely.

Grace: So, do you think the make up of the room really affects ... I guess in Abrams, do you think it affected the decision to publish the book?

Kheryn: Again, I'm not sure who was in the room, but say that I would be very surprised if it turned out that there was a Muslim, person of color, who was a part of buying that book and designing the book. That's all I can say.

Grace: Actually, that ties into the next question which is what happens when a book like Suicide Bomber that is kind of offensive, and it comes in, and you are the only marginalized person in the room.

Kheryn: So, I think first it depends on that person's level and position. I can only speak as someone who has been an editorial assistant and an assistant editor and associate editor, and I can say that power and balance has so much to do with everything because it also has a lot to do with the entry level numbers and how many people of color ... Where we're seeing that imbalance right now is that there are a lot of people of color and marginalized people in entry level positions. Most of the power is up at the top with the white folks, so I think when you are the only person in the room who is marginalized, it's most likely going to be someone who is an editorial assistant, and that is ... It's difficult to speak out against anything that's problematic to someone like your boss, for example, if your boss is the person who brought in something that was problematic, it's going to be difficult to say that to them or even just to the rest of your colleagues in an acquisitions meeting when you're talking to the head publisher and the heads of each of the staff.

Kheryn: Does that make sense?

Grace: No, no, no. It does make sense.

Grace: I've thought about this took, and it is power dynamics. On November 27th, Publisher's Weekly published that article, How I Landed in Children's Books, and it featured about 20 people, I'm not sure how many, people in the industry, and there was only one person who looked like a person of color, and in the comments, I remember reading, and they said the people were complaining why is there so little diversity in this article, and Publisher's Weekly said, "We were trying to find people who had been in the industry for 20 years or longer." And the truth was, there wasn't a lot of people of color that have been in the industry for 20 years or longer. That's really leads to this whole power dynamic that you're talking about because what happens to that one person in the room? What kind of responsibility is given to that person? What kind of stress?

Kheryn: Yeah, more often than not, the problematic book does pass through the acquisitions meeting because it's like that one person does tend to be the assistant and isn't able to say to the publisher, "That's problematic. It shouldn't be published."

Kheryn: So then, it becomes like a ... THere's also another level of you don't want to be the only person speaking for all of your identity, so that becomes its own internalized stress, but then there's also the literal you have extra work to do at this point stress because once it is published and people suddenly start to realize, "Oh, it might be problematic" they're going to go to that one person of color in the room and say, "Can you do this sensitivity read for us please?" Or, as some people will call it authenticity read.

Kheryn: So, it does become more physical work for that marginalized person also to try to back pedal and fix the issues of the manuscript that had been problematic that might have passed through the acquisitions meeting.

Grace: So, it's actually out of responsibility because then the marginalized person has to kind of be the shield for the publisher in a way.

Kheryn: Yeah. Absolutely.

Grace: So, I want to go back to the structure of publishing. As you and many listeners know, my editor, Alvina Ling, is also my good friend, and I remember when she first started as an editorial assistant, and I don't think she'll mind me spilling that the salary for an editorial assistant was extremely low, and that was like the normal. Basically, it seemed like the only way someone could survive with an entry-level salary was to have some sort of other financial support. Do you think that's true today, and how do you think this affects people of color entering the industry?

Kheryn: Oh, that is definitely true because most of the publishing is located in one of the most expensive cities in the world, and salaries, I think, do still start around 30,000, and each promotion doesn't necessarily bump that number up much higher. I'm not from New York. The only reason I was able to stay in New York as long as I did was because I do have my books on the side. I have my side hustle, I would say, and most of the people I know in publishing, either live with their families, their wealthy spouses or with multiple roommates that they have met online, and I did go through the experience of meeting roommates online, and that became like a bit of a dangerous situation, so to me, that means that there's a very specific kind of person who's going to enter the industry, and that limits diversity.

Kheryn: And beyond even race, that also means socioeconomic, who's able to afford to live in New York on such a low salary to work in publishing, and then also location-wise, geographically, culturally, I'm the only person from the Caribbean that I know that's in publishing, for example. And sometimes I struggle because I feel like I came from a different background and I came from a different culture, a different way of communicating, and I wasn't as familiar with kind of like this New York corporate culture.

Kheryn: So, all of that together combines to create very specific kind of person who is going to be in publishing, I think.

PLEASE COME BACK ON WED FOR PART 2 OF THIS INTERVIEW