Episode 69! An Open Letter to Well-Meaning White Women, Conversation with Laura Jimenez

NOW AVAILABLE TO SUBSCRIBE ON ITUNES

Welcome to episode 69 of our kidlitwomen* podcast! Usually, this podcast features an essay about an issue in the children's literature community (Monday) and a discussion about the essay (Wednesday).

In this episode, educator Laura Jimenez and Grace Lin discuss Laura’s essay, “An Open Letter to Well-Meaning White Women” (which can be heard in episode 68) and much, much more.

Read all the kidlitwomen* essays shared in March

Subscribe to the kidlitwomen* podcast on ITunes

On today's podcast you will hear:

Dr. Laura M. Jiménez (2018 – current)* is a lecturer at Boston University School of Education, Literacy program. She teaches children’s literature courses that focus on both the reader and the text by using an explicit social justice lens. Her work spans both literature and literacy, with a special interest in graphic novels and issues of representation in young adult literature. Her scholarship appears in The Reading Teacher,Journal of Lesbian Studies, Teaching and Teacher Education, and the Journal of Literacy Research. Her graphic novel reviews can be found on her blog https://booktoss.blog/. On Twitter, she’s @booktoss.

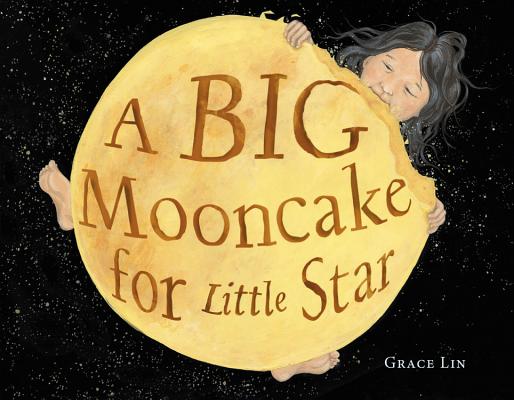

Grace Lin, a NY Times bestselling author/ illustrator, won the Newbery Honor for Where the Mountain Meets the Moon and the Theodor Geisel Honor for Ling and Ting: Not Exactly the Same. Her most recent novel When the Sea Turned to Silver was a National Book Award Finalist and her most recent picture book, A Big Mooncake for Little Star, was awarded the Caldecott Honor. Grace is an occasional commentator for New England Public Radio and video essayist for PBS NewsHour (here & here), as well as the speaker of the popular TEDx talk, The Windows and Mirrors of Your Child’s Bookshelf. She can also be heard on the Book Friends Forever Podcast, with her longtime friend and editor Alvina Ling.

TRANSCRIPT

Grace: Hello. I'm Grace Lin and I'm here talking with Laura Jiménez. Hi Laura.

Laura Jiménez: Hey Grace, how's it going?

Grace: Good. I'm really glad to talk to you further because we were just on a panel yesterday. I'm here NCTE, and we were on a really interesting panel yesterday called Representation Matters. And in that panel we talked a lot about gender issues, which really actually ties right into your essay that you shared for killing women.

Grace: But the first thing I have to talk to you about because it's been on my mind so much, is that after the panel, I went on Twitter to see what people were saying.

Laura Jiménez: As we do.

Grace: I noticed that someone had tweeted about our panels. "Just went to this great panel Laurie Anderson was on it, Samir Ahmed ... " Did I get her name right?

Laura Jiménez: Yeah.

Grace: "Ahmed was on there." She listed all the panelists and then she said, "And I got to take a selfie with Brendan Keeley." And then she posted the big selfie of her and Brendan. And Brendan's an awesome guy.

Laura Jiménez: He's great.

Grace: But he was also the only white guy on the panel. And I was thinking, "Wait a minute, do you see what you just did here?" And I was just a little shocked.

Laura Jiménez: Yeah, it's interesting. You asked, "Do you see what this means?" And I think, "No." I think the answer is absolutely no. Even though we spend an hour and a half ... When was the last panel I mean, it was substantial. And there was ... Lamar and Brendan were the only two men. Lamar is an African American man, and Brendan's the only white man. And the photo choice, the choice to put that up, it's sort of normalizes what we're talking about; where we live, and work, and breathe, and society, where the default, where the norm, the 'neutral' is white, straight able, Cis and male.

Grace: It was just so fascinating because our whole panel was all about trying to dismantle this. And yet the image that she chose to highlight was her and a white male.

Laura Jiménez: And it's not ... I think the point is not that particular user, that's its not that particular, it's the abundance of that. That's typical of its evidence that simply confirms what we see all the time.

Grace: Exactly. I'm sure this person-

Laura Jiménez: Oh yeah, it's not about this personal.

Grace: ... it's not about this person.

Laura Jiménez: No.

Grace: And its not even a judgment of her as much as it is like-

Laura Jiménez: It's an observation of an event that typifies the phenomenon we were talking about.

Laura Jiménez: And I think it's important that women and white women in particular, understand their duplicity and their support of that white male Cis heterosexual able norm, right? That without them supporting it, that no longer has that privilege place. But it takes a majority of people supporting that as normative to make it normative.

Grace: I bet you that it didn't even occur to her that that was happening. I think that just kind of shows how insidious it is. Its like it's a part of us.

Laura Jiménez: Absolutely. I'm a social scientist. And so I do a lot of reading on what makes people do the things they do.

Laura Jiménez: And one of the things that neuroscience has seen in the last year, a couple of years, is they've started to really look at the neurology of empathy, and the neurology of prejudice, and the neurology of group identity. And it looks like we might be hard wired to recognize and favor those that appear most like us.

Laura Jiménez: And so what we are asking, what you and I, and Laurie, and Dr. Price Dennis, and Lamar, and Samir, and Noel, what we are asking people to do, is to work against that instinctual sort of lizard brain immediate reaction to things. We are asking them to do work. And that's why we call it 'doing the work.' I don't think that's incidental.

Laura Jiménez: We spend an hour with people or more than an hour with people asking them to think deeply about their own place.

Grace: And we still have so much work to do.

Laura Jiménez: Yes. Absolutely.

Grace: And that ties in really, really well with your essay. So much of it is about doing the work. And what I thought was fascinating, which I've seen over and over again, and I feel that I myself have been guilty of it as well, is the reaction to be defensive. The first reaction's defensive. Or, I like how you say it, like the rallying cries to be nice, our choose kindness. And there's many different ways I want to talk about this issue with you.

Grace: But the first way I wanted to talk to you about this is, your actual essay yourself, the way that you wrote it so honestly. I really admire that. Yet, I also thought myself being in a little way like cringing, a little, do you know what I mean? Like, just worried like, "Oh, are people going to be turned off by this? Will they disengage from this?"

Laura Jiménez: Absolutely.

Grace: And trying to figure out the balance of who can take that honesty and how can we get people to take that honesty.

Laura Jiménez: I'm an older person, I'm not old old, I'm 52. I went to graduate school late, I had a whole life then I went to graduate school. So I'm sort in this odd space where I'm fairly mid or early career, like I've had an entire life. And I think being an out lesbian forever, growing up in LA as a white presenting Latina. I have had to deal with so much and I have witnessed so much that I am not interested in protecting civility. Because civility has gotten us where we are. The protection of white, straight, Cis, header, normative, able people, is part of what keeps that system in place. And I simply refuse to be a party to that.

Laura Jiménez: I get a lot of pushback, I get a lot of hate mail. I get hate mail. I get people that really don't like what I say. I get people telling me that I'm part of the problem, that I'm too divisive, that I am ... If we, and I don't know who we are, but if we stop talking about race and all the other things, then it wouldn't be a problem.

Grace: Yes, I get that too. Like you're the one making it the issue.

Laura Jiménez: Exactly. If we didn't talk about gender inequity, it wouldn't be a problem. And this is not new, right? Dr. Martin Luther King, which I quote in the piece, he was dealing with this. Where it's not the fact that we lived in a segregated society. It's not the fact that we have the systems in place to keep people out. It's not that we've been fed this line that we have a finite amount of resources, if those resources are rights and ability. It's that we talk about it, that is the problem. And I refuse to take that on.

Grace: So a friend of mine went to a seminar on racism. And we had a really interesting conversation about it afterwards. And she said, "One of her takeaways was that she realized that people of color are not going to be able to solve racism. That white people are going to have to solve racism. Would you agree with that?

Laura Jiménez: Yeah, it's not our problem. I mean, yes, we have our own prejudices, we have our own biases but it's not like people of color are somehow race neutral or somehow don't have those sort of things, we do. In the Latino community, there's all kinds of prejudices about what ... There's colorism, there's regionalism, there's who speak Spanish and who doesn't, there's all of this stuff that's the vestiges of being colonized. So we sound like we're a perfect community, but we don't have the power to solve these issues. We have to somehow convince white folks to come in and believe us and take our messages and then enact them.

Grace: So it's interesting because it is about power, right? That's what I've slowly after having these conversations over and over again, that I realized that it's not even really I mean, it is about prejudice. But what's more underlying is power. Power is the big, big thing that will either equalize us or divide us.

Grace: The thing is that, it's not the people of color who have the power right now. And it's trying to get as you said, people who are white, or the majority. I guess they are not even the majority.

Laura Jiménez: No they're not. We'll have those numbers probably like in 2022. The census is going to happen in 2020, they usually get the numbers out a year later or so. You and I know, we travel the country. We know this is not a majority white nation anymore.

Grace: So we need them to use their power, and we need to convince them that that is a good thing. So, that is where I'm not sure where to go. And this is what I'm talking to you about, about how I admire so much how you're so honest. And I agree with you yet at the same time, I'm like, "But we need to talk to these people. We need to talk and like the tone policing like it's a bad thing, a good thing like, maybe it's a terrible thing but maybe we need it or else it's too easy for them to disengage.

Laura Jiménez: So I think I look at history and I look at the ways that change has actually happened in this country. And change has never happened by playing by the rules, simply has not. Again, looking at Dr. Martin Luther King, he was not the only person involved in the civil rights era. And if you look at the ways up to his death, that he and Malcolm X worked apart, talked together, had very different messages. But at the end of both of their lives, they were starting to converge toward a common message.

Laura Jiménez: Malcolm X was not there to protect anybody's. He was not there to protect the white voice or the white power or anything. He was very confrontational. And I think he should have been. I admired that so much. And I think at first Dr. Luther King was looking at the good white people as if all he has to do is move the veil and they will see and they will enact goodness. And I think near the end of his life, he realized that removing the veil is one action but it is not enough. And I think that's where we are right now.

Laura Jiménez: I think we're at another crossing point in this country that we are trying to convince people, that we are trying to convince white heterosexual able people that their action is needed. And that it does mean that they may feel discomfort, and they're going to see the water that they swim in. They're going to realize that what they've been told and taught and believe and what they really know is not necessarily wrong, but it is not the entire reality.

Laura Jiménez: You and I have a different reality, people of color have a different reality, LGBTQIA people have a different reality. It's not more better, it's different. And we're asking the people that are benefiting from these systems of an equity to recognize the systems of inequity and to change them. We're asking a lot, but I'm still asking.

Grace: That's true. And I guess the truth is, we can't not ask.

Laura Jiménez: No.

Grace: It's a very tricky time, and I agree. I think we are at the time when the veil is lifted now, like you're saying. And now where do we go from here? Because you can't pretend you don't see it anymore.

Laura Jiménez: So an ally isn't just saying I see it, an ally is actually it's a verb. It's doing something, it's enacting change.

Grace: Let's go back to your essay. And we'll go to the specific example you gave in your essay where you talked about how you name the audience, Mark Tyler Nobleman, I feel free to say his name. You said that he was so hurt by the public discussion of his actions of participating in an all white, all male panel. And I guess what it is, is that call out culture that he was against.

Laura Jiménez: Yes.

Grace: So, let's talk about the call out culture. I guess you would identify that you are part of this call out culture.

Laura Jiménez: Absolutely. Yes.

Grace: Why do you think the call out culture is important or needed?

Laura Jiménez: Well, I think and I've only talked for myself, I don't know why other people ... There's a lot of people that are doing the same kind of work. I will say that for myself. It strips the defense of 'I didn't know, I didn't see, I wasn't aware.' It defuses those defense mechanisms. And that hopefully, it will get to a place where people will be able to say, "I messed up, I'm sorry, I will try to do better, and this is how I will try to do better."

Grace: So, he protested. "Why didn't you being the general ... " You who were complaining, "Why didn't you just contact me privately, contact the organizers privately." Why do you say something like that?

Laura Jiménez: Again that's protecting him because his action was public. That action of being on an all white, all male panel, and presenting as all white and all male authors on a panel. That's a public action, that is a public voice that is taking up public space. And he claims to be an ally. Again, being an ally is a verb. You can't claim to be an ally and do exactly the same thing that has been happening forever in this country, and still claim that badge of honor, still want the ally cookie. You can't have both ways, you can't say you're an ally and then not enact that allyship.

Laura Jiménez: And I think because it's a public forum, then the call out needs to be public. If you're going to get public attention, and book sales, and all the things that happens when you're on a panel, and you screw it up, then I think the call out needs to be public.

Grace: One of the things that I've been trying to do and it's been very difficult, is that when I see something such as an all white panel or a panel that's all men, or something like that, I have taken to in my own way, which I actually think is quite mild, I'd say, "Oh, I wish you had had more diversity on this panel." I'll put that on Facebook, I'll put a little comment. And it's been amazing, because what I think I have written as a very, very gentle comment, I have gotten so much angry pushbacks.

Grace: So, it's been fascinating to me in like, "Why didn't you contact me privately?" That's when I get like, "You were putting my organization at risk by doing this." And to me, I feel like I have to say it publicly because I want everybody to see what's going on here? Not that I want to hurt your organization, but like, "Do you see this is something that's going on?" It's not about you, this is about all of us.

Laura Jiménez: Exactly.

Grace: But what is interesting is that, it'll be like three line, and I'll spend like an hour writing. "Okay, now that sounds too harsh." And I'll spend like hours trying to craft something so that hopefully, they realize like ... I'll be like, "I love the organization." And it's true, like, "I think you're a great organization and blah, blah, blah. But this is a lot of white people on this poster."

Grace: So, I imagine that you must get a lot of pushback. If my, very gentle, gentle like little Facebook comment gets people so riled up. I imagine you must get quite a bit.

Laura Jiménez: Oh, yeah. I like the work of Robin D'Angelo, she wrote White Fragility, and she has a couple other books that I liked very much. And one of them, and I can't remember the title of it, I wish I could of off the top of my head. But the cover of it has sort of a Dick and Jane sort of child's drawing.

Laura Jiménez: And I think the thing that Robin D'Angelo does very, very well is explain that particular move, that rhetorical and reactionary move. And what she says about it is that white people, and I think we can say white heterosexual Cis male dominated folks are raised and their reality is geared toward the individual, whereas ours ... you know you're Asian American and I'm Latino, ours is not geared toward the individuals. Our reality is geared to the communal.

Grace: I guess it's because when people see me I feel like I have to represent all of Asian America.

Laura Jiménez: Yeah. We grow up with that and that's our reality. And so when we push back on an organization, they take it as a push back on them as individuals.

Grace: Yes.

Laura Jiménez: Instead of saying this organization and the system is problematic. Now, I'm not letting those individuals off the hook. What I'm saying is, is that a pushback on a panel, a pushback on a public space, a public event, again, should be made publicly. But that defensive mechanism is one where they're defending themselves.

Laura Jiménez: The other thing I think it happens is that the idea of being racist is they imagine, they tend to go right toward burning crosses, wearing hoods, Hitler neo Nazism, and you and I are saying, "There's a continuum of racism. In on that continuum, you are still on that continual." I may not be able to deal with the hooded neo-nazis, they're not going to listen to me, but perhaps I can influence somebody who's closer of proximity that claims allyship.

Grace: I guess that's what is so interesting because I think in one of my interactions with one of the many, many organizations there's that I offended, I had a misunderstanding with one who said, "Oh, but I know you and I and it really hurts me that you think that I'm a racist." And I said, "No, I don't think you're racist. If I thought you were racist, I wouldn't have bothered to contact you or to tell you this or to bring it to your attention."

Grace: Because you're not going to waste your energy on, right?

Laura Jiménez: I mean, Grace, you're not. We're not stupid. We're not going to waste our energy on people that we know are not willing, able and in position to change.

Grace: Exactly. In fact, in a weird way and really it's kind of a compliment. It's like saying, "I know you are an ally, and I know that you can do better and I know you want to do better. This is just my way of trying to say, you made a little mistake here."

Laura Jiménez: Exactly. In education, we talk about ... Dr. Galpin talks about growth mindset. There's a lot of stuff about growth mindset in education. But adults really don't like that. We don't want to think that we also have to grow and we also have space to move. And we also have the ability to change and learn.

Laura Jiménez: I'm not sure what that is rooted in. But when you and I ... although we may be doing it differently, the rhetoric may be different, but I think it comes from exactly the same space. We want people to learn and change and to make room and to broaden the voices and experiences that are available to kids. I mean, you're a children's lives author for a reason. You are an amazing author. Your prose is rich and complex, and you could be writing adult books, no problem, right? But you have chosen to influence children.

Grace: Well, that's what is so interesting. After our panel, we're like walking to the room to recording. We had this conversation which we were talking about ... Was it in Idaho? The teachers who had dressed up like the wall.

Laura Jiménez: Yes.

Grace: The Mexican wall.

Laura Jiménez: The Mexican Wall, it said, Make America Great Again. They wore sombreros and big mustaches like the big ... I don't even know where that comes from, right? And the [inaudible 00:26:43]. 12 teacher.

Grace: I know, all 12, just kind of blew my mind. And that's what scares me. When we talk about races and racism and all these things like we're talking about, I reach out to the people I think I can change. And it's like the people I can't change, I give up. But when it comes to educators, and you see that in educators, and that's when I'm like, "Oh!" Part of me is like, "I give up, I can't help them." But then there's another part like, "If we don't try to reach them, what effect that has."

Laura Jiménez: Exactly. And I think that's probably why I chose the field that I'm in. I chose to get a doctorate in education. I chose to teach teachers, I chose to do this work and I chose to do social justice work with teachers because they have an enormous responsibility. And a teacher education doesn't provide the tools and doesn't support that kind of change.

Laura Jiménez: They will simply re-enact the system of education, the racist homophobic, ables, cis, normative education that they experienced.

Grace: How do you reach teachers?

Laura Jiménez: Luckily when I teach classes, I get the first semester or two semesters. And so I have time. I give them articles to read. We discuss it. I give them especially when I teach the literature, that's where I do most of my social justice work. I give them only own voices. I've been teaching children's literature solely with Own Voices now for about three years, and we have those uncomfortable conversations and I get them used to saying words like white, systematic racism, homophobia. And I get them used to calling their own, recognizing and saying their own identities out loud because I think that's the other thing.

Laura Jiménez: We are used to thinking about our identities because we are not that highlighted norm, they are not. I also think one other thing that came out of that absolute disaster, is that a group of Latinex authors and educators, wrote an open letter and offered time, materials, and education, to that school and that school district. So far, I haven't seen if there is any uptake, it may be happening behind doors, behind private email.

Grace: We can hope.

Laura Jiménez: Exactly, but the fact that the people ... that the Latinex authors, and educators, that was their reaction. It still completely blows me away. I'm in such awe of that.

Grace: I admire that so much and I feel like but it's not for the teachers. It's absolutely the kids that they're teaching.

Laura Jiménez: 12% of that school are Latinex, 12%, that's not one kid. That's a chunk.

Grace: And even if it was just one kid, it's still like ...

Laura Jiménez: And it's also the white kids, it's also the other kids, it's also the other kids of color and the white kids. We need to disrupt, we need to look at, examine, and disrupt the systems.

Grace: Do you ever get pushback from your students, from administrators?

Laura Jiménez: Always.

Grace: What is it that they say?

Laura Jiménez: So, from the general public ... One thing you should know is that on all my social media accounts, I use an image that thin fern, the author of Sumo, fabulous graphic novel that I love, did it for me. And I use that because I don't want my face on social media.

Grace: Yes. When I met you in the panel, and you're like, "Hi Lin." Because I was not expecting you, because I was thinking that you were going to look like ...

Laura Jiménez: I was going to look like a little cartoon.

Grace: Or something similar to that.

Laura Jiménez: Right. I use that. Maybe I should get a new one done because my hair's little shorter. I'm a little older, but I use that very purposely. I do not put my children on social media. I do not put their images, I do not put their names on social media because I have gotten threatening letters from just the general public.

Laura Jiménez: This year and last year, I've gotten a few physical snail mail letters at my place of work because I am at Boston University, and that is a public. They can look me up on the web, and they can find that. And they're not death threats, but they definitely are threats of violence. And again, saying that I am the problem, and then I need to be shut up. There's that tenor to them.

Laura Jiménez: In the classroom, it's a little different, because that's one on one or that's face to face. And I feel like when I do get that pushback, it's actually a good sign, because that's when students can verbalize these things that they've not been verbal about. That's when students can start working on disrupting that. If they don't say it, we can't work toward a change.

Laura Jiménez: They say that they feel threatened or they feel isolated or they feel targeted. The targeting is a big one. They feel targeted by the fact that I say that education is a system of inequity. And they feel like I'm targeting teachers. And I'm like, "That is correct."

Grace: I don't want to feel bad because I'm white. It's not fair that I have to feel bad just because I'm white.

Laura Jiménez: Exactly. And it's that idea of as individuals they are not used to feeling uncomfortable because of issues of identity. They're not used to being questioned and pushed to think about what they value. This person on Twitter I'm sure had no intention of highlighting the one straight Cis heterosexual white male on that panel, and yet they did.

Laura Jiménez: I think the argument of intentionality is another issue of civility. I don't know your intention. I can't know, that's a secret, and that is buried in the black box of your consciousness. But I can see your actions, and your actions have an effect. That's what I can deal with. That's what I can, that's what I know. And so I don't care about people's intentions, I just can't.

Laura Jiménez: That is something my students really don't like because their intention is not to be racist but their words or actions are racist. And I'm not going to let them off the hook because of the intentions, because I don't believe that. They didn't burn a cross on my lawn but these people, these 12 teachers still did a racist thing.

Laura Jiménez: I don't understand how you can do that. That's a lot of crafting. That's like heavy duty glue gun crafting. That was intentional.

Grace: That's a lot of time and know one, not one of them had thought, "Hey, maybe this isn't a good idea."

Laura Jiménez: And they're not alone. I mean it's not unusual. It's not unusual at Halloween; to see the geisha, to see the rice paddy hat, to see the sexy Mexican, to see the Pocahontas. We see those.

Grace: Which I have bought into to. I remember my college years. I'm like, "Oh, you could just cringe at all the mistakes that you've made." I cringe at the mistakes I've made.

Laura Jiménez: Exactly. Oh yeah. I'm really happy that I'm 52 and the internet wasn't around when I was younger. "Are you kidding me?"

Laura Jiménez: I do believe in ... I'm not religious, but I do believe in redemption. I do believe in change. I wouldn't be in education if I didn't deeply believe that people can learn and can change. But I need to see the action.

Grace: I agree and I think that's the thing that I want people or friends, allies, I think that's the whole thing. I think sometimes the people that I know feel so defensive and they feel like I condemn them or something like that. And I'm like, "No, no, this is our opportunity to move forward." It's like you said, "I believe in change and we all have to do it together," kind of thing.

Laura Jiménez: Exactly. Alex Gino who wrote 'George' and now their latest novel 'Jilly P; He doesn't know everything,' I think it's the title. I did a panel with them, and their views of an apology is so wonderful. It was an apology has parts to it. And one is recognition. I did this thing, one is an apology; I recognize that thing hurt you, and a promise I will try to change that thing. But I love the fourth part whereas the person that did the hurt goes away from the person they hurt to do the work

Laura Jiménez: I can't do that work for them. You can't do the work for your friends. You can point it out. You can give the resources but they need to go do it. And I really like that that model.

Grace: It's a tough thing.

Laura Jiménez: Its not an easy. That's why it's called the work and not cake.

Grace: A cake would be nice too afterwards.

Laura Jiménez: Absolutely.

Grace: This has been great. I think this is a really important thing that needs to be discussed. You were talking about the objectification of male ... male people of colors bodies, especially in the children's book industry and how we're interacting. I hope that if people listening go and listen to my conversation with Betsy Bird, where we talked very much about perhaps how there's a lot of inappropriate behavior about male authors. And I think you touched upon a part that goes even a little bit deeper, whereas if you're talking to the male author. Do you want to talk about that a little bit.

Laura Jiménez: So, what I observed and what other people have observed, and I was in conversation with them is the ways that white women place hands on men of color, authors of color specifically. And I actually wrote about it, I actually said, "Listen, this is the thing that I have seen. I have seen white women/black men's hair their dreads, their braids, their head. I have seen them nestle up beside them and press their breasts into their arms to stroke their biceps, to literally put their hand ... I don't know what you call that, lower backs or upper butt space. It should have a name. But they put their hand there. Again, none of this is incidental. It's not like they accidentally tripped into them put their arm up against there boobs, up against the guys arm! This is not accident, because it stays there. It stays there while they're taking the picture. It stays there while they're talking to them.

Laura Jiménez: And I think we need to talk about consent. And again, it's this change mindset that adults can have as well. We want kids to change, we also have to be willing to change.

Laura Jiménez: And so I actually wrote out consent. If you want to, if you want to have that kind of interaction, then you need to say out loud, "May I touch your head, may I stroke your bicep. May I lay my hand on your lower back upper but region. May I press my breast up against your arm."

Grace: And it sounds so ridiculous.

Laura Jiménez: Exactly. And if you don't get an enthusiastic, "Yes, please," a verbal consent, then you shouldn't do it. And if you can't ask, then you really shouldn't do it. This is how we should be treating each other. You should ask and wait for permission to touch somebodies body, in any circumstances. Maybe if there's a bus accident involved? Yes. But other than that, in these professionals spaces, authors are professional. You guys are here for your job. There is no reason.

Laura Jiménez: And yes, I am not leaving African American women and other women of color out. The fetishizing of women's hair, of women's of color hair, is a whole, there's dissertations on that. It's a whole problematic. I'm sure people come up and start trying to touch your hair and how thick and Asian it is, or whatever they say. Don't lay hands on people before you ask them.

Grace: Luckily, I haven't had that issue. But I think that because we are in a female dominated industry, that's why I feel like it's a much more of a male-woman issue.

Laura Jiménez: It could. Malinda Lo has a great piece on her website about the fetishizing of lesbians in these public professional children's literature spaces. And she gets into that. She's done an excellent job. Specifically, I was an observer of white women putting hands on black and Asian and brown men. And I found it very disturbing. I'm not going to call any particular author because it's not their problem. But I saw many of these men shrinking away, trying very hard to not be in bodily contact, and these women simply don't see that.

Grace: It ties back to my conversation with Betsy Bird about how it's like the hot men of children's literature. But it's a very very odd power struggle because it is a power thing. It's like the author feels like they have to ... they don't want to make the librarian upset or hurt their feelings all because they feel like the librarian who was going to buy their book, promote their book, they're the ones with the power.

Grace: And she said, "It's so interesting," because she bets that ... Then the library sees that way. They think, "Oh, the author is the one with all the power."

Laura Jiménez: And again, it's this issue of intentionality. Do I think these women intend to make these men uncomfortable? Do they intend to fetishize their bodies? I don't know. I don't care. The fact is, they're laying hands on men of color, and white women laying hands on men of color has a disastrous history.

Laura Jiménez: I mean, let's go back to Emmett Till. Emmett Till was killed on the accusation of a white woman who later ... that woman retracted. And these men have that in their heads. I think we need to be aware that we are not on an equal playing field. It is not easy. It is not straightforward. But I think if we had ... Like you said, if we had a playbook we just had some guiding ... We just had some basic, decent guiding, guiding questions. If I want to touch you, I should ask you. If I can't ask you, maybe I shouldn't be touching you. If I ask you and you don't give an enthusiastic yes, maybe I shouldn't do it. That's not that hard, but it does need to be conscious? And that's what I'm asking for people. I'm asking people be conscious.

Grace: That's kind of the root of it. We do so many things unconsciously. And it's just trying to keep that consciousness at all times, like being vigilant all the time, and it's really, really tough. And that's why we call it the work.

Laura Jiménez: The work. And I think we need to remember these are professional spaces. They're professional spaces for us as teachers and teacher educators, but I think for authors these are ... Y'all are on display, your contracts call for these kinds of engagements. This is your job. And I think sometimes we forget that.

Grace: Well, this has been wonderful. Thank you so so much for coming on the podcast. I can talk to you for hours. You're so smart and I feel I can learn so much from you. But we've been talking for like 46 minutes. I might have to break this podcast into two.

Laura Jiménez: Just take things out.

Grace: No, no, I don't want to anything. I feel like everything you said was so important for people to hear.

Laura Jiménez: Thank you.

Grace: I'll end it with the two questions I ask everybody.

Laura Jiménez: Okay.

Grace: The first question is, what are you working on? Is there something you'd like to share? Like another lecture or something like that, you'd like people to hear about.

Laura Jiménez: Actually right now, I'm getting back to blogging. I spent the last couple of months, almost a year, focusing on academic writing, which means writing for journals, writing chapters. And so now I've sort of done that stuff, that's all in the works. So I'm going back to writing my blog, which I'm really happy about. So, people can go and check that out. You just look up book toss on the internet and you get to my stuff.

Grace: It's Book Toss blog.

Laura Jiménez: That's it. And so I'm doing that. I will be doing with Ed Campbell and some other folks, highlights, event. But that won't be until the summer.

Laura Jiménez: I'm teaching. I teach at Boston University. It's just business as usual.

Grace: So that leads to my second question. Usually I talk to authors. It's a little bit different but I still think that ... I usually ask them what their biggest publishing dream is, with the idea that most times ... I have a lot of women on the show. And one of the things that women are bad about is naming their ambitions. So I would like to know what is your biggest dream? What's your biggest hope that you hope to accomplish with all that you're doing? What could happen that would make you feel like, "That's it, I did it."

Laura Jiménez: The big thing?

Grace: The biggest.

Laura Jiménez: The big thing.

Grace: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Laura Jiménez: all right. I want to create an organization, a nonprofit, something that educates teachers that are in the field about critical race theory, queer theory, feminist theory, and children's literature and how to bring that into the classroom and supplies them with books. Because I can teach my courses and other people that teach courses like mine in their universities. We can get the buy in of teachers, and we can go out and we can do professional development and we get the buy in, they see the value. But there is not enough funding in public education to create the libraries they need to do the work we're asking them to do.

Laura Jiménez: So that's what I want to do. I want to make it possible to create libraries. And it may be temporary libraries. In other words, teachers are going to teach a unit on something. We throw together a couple boxes book and ship them off and they ship them back when they're done. So, that they can get the books like yours into kids hands. And they can do critical reading and they can learn about stuff that they don't know anything about.

Grace: It's amazing.

Laura Jiménez: That's what I want. That's the big.

Grace: Yeah.

Laura Jiménez: I have no idea how that's gonna happen.

Grace: But I hope, I really hope it does happen someday. So thank you again.

Laura Jiménez: Thank you.

Grace: Goodbye.