Episode 73! I is for Inclusion, Conversation with Padma Venkatramen

NOW AVAILABLE TO SUBSCRIBE ON ITUNES

Welcome to episode 73 of our kidlitwomen* podcast! Usually, this podcast features an essay about an issue in the children's literature community (Monday) and a discussion about the essay (Wednesday).

In this episode, Padma Venkatramen and Grace Lin discuss Padma’s essay, “I is for Inclusion,” (which can be heard in episode 72) and much, much more.

Read all the kidlitwomen* essays shared in March

Subscribe to the kidlitwomen* podcast on ITunes

On today's podcast you will hear:

Padma Venkatraman has lived in five countries, worked as chief scientist on oceanographic vessels, and even spent time scuba diving before becoming an author. Her novel, A Time to Dance was released to five starred reviews and received numerous awards. Her two earlier novels, Island’s End and Climbing the Stairs, were also released to starred reviews, and were ALA/Yalsa Best Books, Amelia Bloomer, CCBC, Booklist Editor’s Choices, and won several other honors. She has spoken at Harvard and other universities; provided commencement speeches at schools; participated on panels at venues such as the PEN World Voices Festival; and been the keynote speaker at national and international conferences and literary festivals. Padma is American and lives in Rhode Island. Her newest novel THE BRIDGE HOME which is an 'Oliver Twist meets Slum Dog Millionaire' story and has garned many starred reviews is out in stores now.

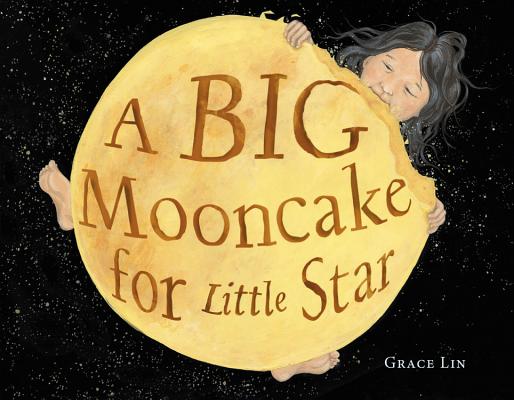

Grace Lin, a NY Times bestselling author/ illustrator, won the Newbery Honor for Where the Mountain Meets the Moon and the Theodor Geisel Honor for Ling and Ting: Not Exactly the Same. Her most recent novel When the Sea Turned to Silver was a National Book Award Finalist and her most recent picture book, A Big Mooncake for Little Star, was awarded the Caldecott Honor. Grace is an occasional commentator for New England Public Radio and video essayist for PBS NewsHour (here & here), as well as the speaker of the popular TEDx talk, The Windows and Mirrors of Your Child’s Bookshelf. She can also be heard on the Book Friends Forever Podcast, with her longtime friend and editor Alvina Ling.

TRANSCRIPT

grace: Hello, this is Grace Lin, and I'm here with Dr. Padma Venjatraman to talk about her essay, I Is For Inclusion. Hi, Padma.

padma: Hello, Grace.

grace: It is so good to see you.

padma: It is very lovely to see you too.

grace: This is nice. I'm actually doing this interview in person, which is very different. Usually I'm doing these things online.

padma: It's so much nicer in person. I think I'd be nervous online.

grace: Let's talk about your essay. There's so much to unpack in this essay. Why did you write this essay?

padma: Margarita Engle, who's a friend of mine, actually told me that you were doing this, and it was just such a wonderful thing and such an important topic to talk about. I thought I would ask you if I would be included, and you said yes. It was a privilege to write about it, and it was important I think because I think my point of view is perhaps different from many others, even many other authors in this country.

grace: Why did you specifically decide to write about inclusion do you think?

padma: I think one of the things that had happened sometime before the essay, or at least it was very much in my mind, it wasn't actually chronologically that close, but I thought I was asked and invited to do a keynote at a conference. It seemed like everything was squared away, and then after that I got an email from the person who had invited me saying, "Oh, we're really sorry, but we're getting somebody else to do the keynote." He was a white male. She said, "I'm sure you understand, because he won all of these awards." On the one hand, I said I understood, and I guess I could, but on the other hand I was a bit stunned, because the conference was actually supposed to be about diversity. They had a white male speaking as their keynote speaker. When I went and they said, "We'd still really love for you to come and be on a panel and also do another talk."

grace: Let's backtrack for a bit. I was listening to this with an open mouth. I'm gonna recount what you said, just to make sure, and you correct me if I get this wrong. You were invited to keynote at a diversity conference. At least you think you were invited to keynote at a diversity conference. Then I guess mid-planning you received a phone call.

padma: No, not a phone call. I had actually gone ahead and planned a whole lot of events around this keynote to do. After everything was set in stone on my side travel-wise, the person whom I had been in contact with and whom I thought had invited me sent me an email to say, "Oh sorry, no, actually we're not going to have you be the keynote."

grace: How much time was this before the actual conference do you think?

padma: It might have been a couple of months, but the thing was that I had gone ahead and planned several other events and had actually my whole family take time off because we thought we would go to this nice part of the world, I'm not going to say where it was, and do all of these other things.

grace: You thought you were invited to do a keynote at a diversity conference. A couple months before the conference is supposed to take place, after you had already made all of your arrangements, including taking time off for your family so that they could come with you, you received an email from the organizer, who said, "We were able to get another author to be the keynote." Did she say, "Do you mind stepping down?"

padma: No. I think they said that there was some confusion, because I had written something, I don't know what it was, and they said there was some confusion and they had this person. Actually she didn't even say there was some confusion. She did say, "Hey, you know what, we got so-and-so to do the keynote, but we would still love for you to come and do the panel and do something else." She didn't say step down. She just basically said, "I'm sure you understand that so-and-so big shot white male," and he is a big shot white male, he's a wonderful writer, but-

grace: It's not about the white male authors, it's not to diminish what they accomplish. This is more about the fact that the email that you were sent that they said, "We were able to get this white male author, and I'm sure you'll understand that he's gonna be the keynote. Will you please still be doing a workshop and a panel?"

padma: The person who wrote to me was a woman.

grace: This is a diversity conference.

padma: This is a diversity conference. When I showed up, and that was something that I shouldn't have been shocked because of everything that had happened, I was the only author of color that whole day. I had suggested, as I always do, especially if somebody invites me to do a keynote, I say, "Here's a panel I would love to be on. Here are other authors," and they are invariably authors of color, and women, I have to say. They haven't taken any of my suggestions, but by that time I also didn't follow up on it, quite frankly, because I was upset and I was wondering should I still go. Then I decided because I had all these other things I would still go. As I said, I was the only person of color at that conference. There was no other author who was on the gender spectrum as well. I was a female. There were other females. There was no one on the LGBTQ-plus spectrum.

grace: As a diversity conference, this very much failed.

padma: The odd thing was that the keynote speaker got a standing ovation, and that to me was also stunning.

grace: There's so much to unpack here. First, the one thing that keeps coming back to me is that the organizer said to you, "I'm sure you'll understand." That is such a remark that is so hurtful, because it's like, "I'm sure you'll understand," because not only did she assume that you would see her point of view, she assumed you would see her point of view, and she obviously didn't really see your point of view. Then what's even more interesting is that you still agreed to go. This is not a judgment of your decision to go, but more about how ... Let's take the race element out for just a moment. I feel like this is, or maybe it is part of the race element, but this is how we as women, maybe as minority women, work. We were insulted, yet we still do the person who insults us a favor.

padma: It was that, but I thought about it a lot, and I felt ... After I went to the conference I was glad that I had gone, because I felt like I had contributed, and at the conference did speak out at the session and at the panel and point out that I was the only person of color. I don't think that comment perhaps reached everyone. Perhaps it reached very few people. The lack of diversity at that conference shocked me. I did speak out about it. I wondered. I wondered, "Okay, should I just say I'm shocked, I'm insulted?"

padma: As you were speaking, I remembered this, she said, "The committee decided not to." She wasn't apologizing at all. She was pushing the blame onto, "The committee decided not to invite you," which was very odd too, because I felt like if you do something like this, you need to take the responsibility and say, "I am sorry." She didn't really say that, I don't think, at least in my memory, and I don't think I even have those emails anymore. That was my understanding of the situation.

padma: I did go because I felt like I wanted to say these things, and these things were not gone, and they were perhaps even more important for me to still say them. I don't know if it was the right decision, because I didn't speak up and tell them how insulted I felt. Also, it was not just me. There were so many other things. On the post, one of the points that I made was it's not enough to just invite people who are diverse and put them on a panel, it's also important to include our suggestions when we say, "I'd like to be on a panel and here are these other authors in the region. Can you invite them?" or, "Here's somebody I think would be great for a keynote." At least listen to our suggestions. At least write back and say, "That's a great idea, but maybe we ... " Whatever. Listen to us when you're planning the event too. Ask us when you're planning the event. Reach out to us and say, "Who do you think would be good?" because maybe we would suggest people that you would never think of.

grace: When you went to that conference and you pointed out that, "At this diversity conference I am the only person of color," how do you think the people in the audience received it, the few that you were able to reach?

padma: I don't know if anyone was reached. I'm hoping there were a few that were reached. The comment, to me it was never acknowledged. No one said, "Oh yes, that's true." No one said, "Oh my goodness, we're shocked." Whenever there were questions after the panel, and I remember that it was a long time ago, but I do remember that no one raised this issue during the comments or during the question and answer session.

grace: How did they talk about diversity?

padma: I think all they did was ... The keynote speaker did speak about diversity as a thing, as an important point, and certainly We Need Diverse Books has done such a good job of putting so many talking points up there. I think now it's easy for anyone to speak about the issue, but there's theory and there's practicality, and there's often a divide between those two, even in science. There was certainly a divide at this conference.

grace: I think that's fascinating, because there's this whole own voices movement going on. I always have very mixed feelings about it. When it first came out, I was like, "People can write what they want." I slowly started to realize. I started to change my mind about it. One of the big things that made me change my mind was because of all the school visits I do. I started realizing I do so many school visits and how important it was for the kids to see an author that looked like the work that he or she did. There was just an episode on kidlitwomen where Karen Blumenthal talked about how she noticed that all the nonfiction award winners tend to be white, and a lot of them have won for civil rights books.

padma: Wow.

grace: I was just thinking about how does that feel to be a black child in a school and an author comes in with their civil rights books and the author is white, and that happens year after year after year. How often does that happen, and what message does that send to the kids, that their history cannot even be written by somebody who looks like them? I think that's where it becomes a very, very important point, where kids have to be able to see people who look like them. That trickles down. That's where things like these conferences are so, so heartbreaking, because we're talking about these issues, yet we still can't even get more than one person of color in the room.

padma: Exactly. I was stunned to see that, because Grace, you've been talking about diversity for years, there are so many of us who have been. In the beginning we were isolated. I think We Need Diverse Books brought a group that was together, and they did so much good work in terms of pulling together statistics and so on, and yet this goes on even now after they have done so much work. I think that shows how much more work really needs to be done. Even at that conference the keynote speaker said something that I disagreed with so much. He spoke of books by diverse authors and said how a child who was of color let's say would be able to pick up one of those books which had another child of color on the cover. His viewpoint seemed to be like, "Hey." That's part of it. That is part of it, that the reader sees herself or himself in that book. You also need to see that a book like the one that you wrote, or so many of the ones that you've written, the fantasies are just phenomenal fantasies, any child, they're for every child. They're not just for a child who looks like [inaudible 00:15:08].

grace: It goes back to the windows and mirrors. They're both really important. The mirrors, so important, that children can see themselves. The windows, the idea that what we call mainstream, which is basically white American, can see something other than white America. It's such a interesting thing that we're talking about, the idea of theory versus practice and how can we get our community to go past the ideas that we all say we are supportive of.

padma: The one thing that I thought of after that keynote was, and it happened later, my friend Jackie Davies, she was on a panel with me, and she actually said, "I want to step down so that there is a place for someone of color to be on this panel." I had never, until then, seen a person actually do that. I thought that was such a wonderful example that she was setting.

grace: This was at another conference?

padma: Yeah. It was much later at something else. It was completely unconnected. She just said, "I've been listening a lot and I've been trying to educate myself about diverse issues," and there was the practice. She said, "On this panel we have ... " They had me, and I don't remember who else was there. What I remember so significantly was that she said, "I as a white woman am going to step down and give a spot to someone else." It just made me see that Jackie Davies is not someone who just thinks about these things and mouths these words. She's actually doing something about it. That made me really respect her so much more.

grace: That's a perfect example of how we can take the words we say and actually mean them. I think it's fascinating because I had another interesting conversation with Linda Sue Park, and how we talked about so much of what we, when we talk about diversity, is about people like, "I'm gonna support others. I'm gonna support others," but what really shows your real commitment to these issues is what you're willing to sacrifice. Here Jackie was willing to sacrifice her place on the panel. That is a real, I guess, ally.

padma: Yeah. I really hope that when my time comes, if it ever does, that I'll also be able to see it and I'll be able to sacrifice and step down or move aside, because I think in some ways all of us have privilege and all of us are in situations without privilege. I think there's so much more to us than what maybe is on the surface that people see. When you see me you might think, "Okay, she's a woman and she's of color," but you don't know other things about me. You don't know that at one point in my life which was very important to me and shaped how I think about things for a very long time, my family, which was just me and my mom, who was divorced, or separated, from my father, it was very uncommon in India, struggled to make ends meet. That puts me in a situation that is different from even several other South Asian American authors that I meet who gave from middle class or relatively wealthy backgrounds. I didn't come from that.

padma: There's all this other stuff as well that plays into who you are. Religion is another issue that you never really see, which is also important. All of those things can be sometimes maybe barriers or keep you out of or include you in circles because of commonality in terms of, I don't know, religion or economics or something else. I think that's also important to me that we recognize as a community is intersectionality, which is the intersection, for anybody listening to the podcast who doesn't know, just the intersection of different things.

grace: I think intersectionality is pretty important, because that's when you talk about individuals and seeing us as individuals, that's part of seeing us as individuals. What made me laugh when I read your essay was about how you've been mistaken for other Indian American authors. Recently I was at a gallery show with my friend Lisa Yee. I'm used to getting mistaken for other Asians. Lisa has very, very short hair. She does not have glasses. We're of a different age. We dress completely different. Yet we were constantly mistaken for each other that whole evening. I remember being so annoyed because it's one thing if you've mistaken me for another Asian woman with long hair, another Asian woman with glasses. Okay, I get that, but the fact that you mistaking me for her, who is so different looking, it means that all you see is race.

padma: Actually, we're at NCTE now as we record. One of the first things that happened to me when I came here was, I won't say her name or anything, but another author saw me, and I was with my editor at the time, and immediately mistook me for an editor who is Indian. I know who she meant. I've seen that person. She's very different. She's very, very tall. She's extremely skinny. She's gorgeous. I won't describe her more. She said, "Oh, I know you." She seemed to know me. I thought, "Oh my goodness, maybe I've met this person before." I hadn't met her. I gave her this big smile like I knew her. I was thinking, we all have those moments, "Oh, who is that person? Maybe I should just be polite." Then she said this and I thought, "That's why I didn't remember you, because I've never met you before." Then it's happened to me twice after.

padma: The lovely thing is that now we have such a huge bunch of South Asian authors out there. When I started, which was when my first novel was published, which was about over 10 years ago now, and it's still in print, yay, but when that first came out, there was just me and I think Mitali Perkins and Uma Krishnaswami, and that was pretty much it. The two of them had been working even longer than I have. Now there are so many. There's Aisha Saeed. I don't know, I can name ... Yesterday at dinner there was, oh gosh, Marsha [Bajaj 00:22:30], there's Sayantani DasGupta. I don't wanna say too many more names because I'm sure I can't remember all of them now, but there's so many of us, and that's wonderful. Yeah, we all have black hair, and I can see sometimes with some of them, again, yeah, okay, we both have black long hair or whatever, but look.

padma: It's not something I would never want that somebody who did that kind of an error would never speak to me again because I was so worried or upset or anything. I don't think it's a deep sense of being upset, but it's something that happens a lot. I think trying to see beyond, like you said, it's not just your Asian features. There's more to us than our skin color and our dark hair. There's all these other things. Look at what we're wearing. Look at the style of our clothes. Look at our name tags.

grace: Like I said, in general I usually don't get upset about that. I was at a different conference with Kelly Yang. She is Asian. She's much taller than me, but she has long black hair and she has glasses. We took a photo together, and I remember showing the photo to my daughter. She was like, "Mama, that person looks exactly like you!" I get it. I get it. I do get it. Oh gosh knows I've mistaken many people.

padma: I could see that, but I don't know, I think we all, I was talking about that yesterday on a panel, was we all make mistakes. It's to look and to try to move beyond that. Nancy Paulsen, who's my editor, and who's also Jackie Woodson's editor, was actually talking about a panel where I guess there was Jackie and Rita Williams-Garcia and all of these other wonderful African American women of color, and they were talking about how they're constantly now mistaken. People will walk up to them and say someone else's name.

grace: It's interesting. I'd be curious to see how much that happens to people who are white, because, I don't know, it's interesting. I have a feeling that it is race that does it. I think there's a lot of people who would like to argue that it's not the race, but I think it is.

padma: I think it is. The only other person that I've ever heard tell me that this happens to him, it was Brian Selznick and Sandy C. Alexander, oh gosh, I should know his last name. I can see his books in front of my head. Anyways, he does look like Brian Selznick. I guess people mistake Sandy for Brian. In their case I like to think they are both, their body types and the way they dress, and they both wear glasses that are almost the same frames, I could see that.

grace: I guess that was the point I was trying to make about Lisa and me, because I was like, "We really do not look anything alike, so if you've mistaken us, then all I can assume is that it's a race thing." This doesn't really lead into my next question, which actually doesn't have anything to do with your essay, except for the fact that I had a interesting conversation. Do you feel that you've been mentored as an Indian author or do you feel like that you've had a lot of mentorship?

padma: No, I don't think I've had a lot of mentorship as an Indian author, no. Can you ask me again a little more maybe? Because I'm trying to think what ... No, I don't think I have, because I felt like I was isolated, I showed up, and there I was.

grace: The reason why I ask this, and I'm sorry to branch off of your-

padma: No no no, that's fantastic.

grace: ... your essay, but because you're in front of me and I was like, "Oh, I really wanna ask you this," because I was asked as part of my panel, tell me about your mentors.

grace: I remember you told a very interesting story when we talked last, about you went to a meeting.

padma: Yes, I was just thinking of that. I went to a meeting, and again, I won't say too much more, except that I was the older South Asian woman on that panel, and the other authors were all new, young and upcoming, and they asked me if I'd mentor. I think I put a lot of effort into it. I had a lot of other things I could've done. I was delighted to be asked. I was honored to be asked. I read all their books. I had questions around it. I wanted very much for us to meet ahead of time, for us to discuss these questions. None of this happened. The worst thing was that I felt like when I spoke on the panel, A, one of the big differences was that I had not grown up in this country, all of them had, there was the economic issue as well. I did feel that sense of I had grown up in that environment where I had lacked economic privilege for a while in my life. I certainly am fine now and have been for many years. That's important too. There were all these other issues.

padma: On that panel, the worst thing was I felt that when I left there was no sense of thanking me for the time that I had been on. It was one of the times that I felt the most left out and the most hurt, because I felt almost like I'd been stabbed in the back by my own, which somehow feels worse, which is maybe its own kind of, I don't know, racism or something.

grace: Cutting betrayal.

padma: Yeah, I felt betrayed. I have noticed that now that other authors of color will reach out to me and be like, "Oh hey, do you have a question? I'm researching this." For instance, "I'm doing something on people who are incarcerated. Do you have something you could help me with?" Yes, I actually take the time to connect them with somebody, two of my friends who are working with people who are incarcerated. There's no thank you. I feel bad, and I usually end up apologizing to the friends, because I know there's been no thank you from that person and saying, "I'm sorry that person didn't say this," or whatever. I think that it's sad. I think we need to be able to be thankful. That's just such a short word. If you can write me a long note asking for my help, say thank you.

grace: It is a thank you. What it is it doesn't feel like connection. It feels more like, "I need something." I guess that is where there is a blurry line of support versus support mentorship and just giving somebody, handing things out, handing out all the knowledge and all the things that you worked so hard for. There's a part of you that wants to cultivate and nurture. Yet at the same time you worked really hard for all the things that you've worked for. Just to give it away to people who don't wanna have a connection is hard.

padma: It is hard. The one thing that worked out very nicely was that We Need Diverse Books has the mentorship program, and I read a lot, and on that mentorship program I ended up really liking something that was by another, actually there were two South Asian authors whom I've really liked both of them very much. Then I did ask myself actually, "Am I gravitating towards these people because they are so much ... " Both of them had Indian backgrounds. I thought, "Oh, am I biasing towards the Indian young authors on the panel?" Then I talked a lot and I thought a lot and I ended up anyway informally mentoring a lot of those people that I liked, even though I didn't pick them as my mentee. I think some of them were thankful. That was lovely to just have that feeling of somebody else reciprocating and being happy. Some of them weren't, obviously. I think if I reach out to you and I say, "Hey, I loved your work. I'm sorry I wasn't able to take it, but here is some feedback," that's not expected of me. That's not expected of us as mentors or on this program. When I go the extra mile, it's nice to be appreciated, I think. There's a part of you that does want somebody to just say, "Yeah, that's nice of you."

grace: I guess it's just the idea of I want to help and I want to make this community better, yet I also don't wanna be just somebody's steppingstone. It's interesting. It's a interesting dynamic. It's something that I struggle with all the time, because I do feel strongly about improving the community, yet I also have these selfish desires, or maybe not desires. Selfish insecurities, I think that's a better way of putting it.

padma: I think my insecurities probably ... I've been very lucky now, I've got, what, one book that got starred reviews at five places, another book that got starred reviews in five places and is no longer in print, which I'm very, very, very grateful for all my starred reviews. When all of these come in, I think the one thing that happens sometimes is I get a little ... My insecurity is to think I've never won a huge prize and maybe never will. I think sometimes, oh, if one person who looks like me wins one of them, then none of us ever will, because the community as a whole tends to find one person and then give them something again and again and again. I think that's my insecurity.

grace: I would agree with that.

padma: I will be delighted on the one hand, but on the other hand I would be like, "Oh, why isn't it me?" and, "Oh, will it never be me now?"

grace: Yeah, or a person of color or an Asian person wins one of the big awards this year, you're like, "Ah, then I gotta wait another 10 years before I get a shot, because that's the Asian winner until they'll let another in in another five, 10 years, and that's when I might have another shot to get in." I completely understand. These are the insecurities that we deal with that I'm not proud of. I'm very ashamed of it. That's I believe also honest.

padma: I was thinking, and I think I was digging out, and yeah, there's my insecurity right there. I think, "Oh, please please please let me ... " I hope, if I ever did win one of those big prizes, I think I would say, "You know what? Thank you very much, and look at all these other people too," because there is that tendency. We put people on a pedestal, a bit like show business. What I think of is there are two things. Going from science to this, I think one of the big differences, this is a very, very subjective field, and yet we try to think that it's subjective. The way we speak, the way I speak, "This is a great book," and when really what it means is, "I love this book. I think it's a great book." I think we tend to do that, "This is a great author. This is the great Asian author." We need to move a little away from that. There are so many brilliant, wonderful authors. I don't think every person has won an award. They are so deserving of it. There'll always be other books that are deserving that don't get it maybe or whatever else. I think that's something that's important for us to recognize and celebrate also as a community is to respect those who have been toiling in the trenches for a long time.

grace: Definitely. I guess that was the one thing that was really interesting. When We Need Diverse Books came out, it was great because it brought all this attention to diversity in our books, but I think people thought, people who were outside of what we've been doing for years, that, "Oh, there's none." No, it wasn't that we didn't have diverse books before. We had diverse books. We had diverse books, a lot of them. It's just nobody was reading them. It was almost like I wanted to change it, like, "We need to read diverse books." It's been a interesting journey. I do believe that things are getting better. I do wanna do my part.

padma: I think I always wanna acknowledge the people that went before. Mildred Taylor, Sharon Draper, Nikki Grimes. There are so many of these people that have maybe not won the big awards in the field but have done brilliant, brilliant, marvelous work that I think is very, very deserving.

grace: Sorry to have gone off a little bit on a tangent.

padma: No, it was wonderful.

grace: I think it's time for the last two questions of the podcast. The first one is very easy. I want to know what you're working on and what would you like to share with the listening audience, any new book or new project, either that just came out or that's coming up.

padma: The Bridge Home, my first little grade novel, is coming out in February, so I'm really excited about that, because it actually draws on the time that we were not ... Actually, it's not my life, but it looks at people who are really, really in dire circumstances, so dire poverty in India and hunger. It's the relationship and the friendship between four people, four young children. I love it. I love my characters.

grace: Aw. That sounds great. February you said?

padma: Yeah, The Bridge Home.

grace: The Bridge Home. We'll look for it. Then the second question, this is a question I ask everybody who comes on the podcast, and it's what is your biggest publishing dream. Now I ask this question with the idea that I want you to shoot huge, big, not just, "I want people to love my books," because we all want that, I understand. The idea is that I want us to feel like we do not have to be ashamed of our ambitions, that we can name them and go for them. What is your biggest publishing dream?

padma: Oh gosh. My biggest publishing dream would be that there would be libraries that would be filled with great diverse books, including diverse books that have gone out of print, that we would never let great books go out of print, that we would always somehow keep them there. I think that's important because some of them just get dropped by the wayside, and there are so many brilliant, brilliant books that I've read.

grace: I think that's a great dream, but how about you, a personal publishing dream?

padma: Oh gosh.

grace: What is your own personal publishing dream?

padma: I would like to leave lots and lots of books that just stay on after I pop off, that I read and that are loved and that are celebrated after I die.

grace: For your books to live after you.

padma: Yeah, I do. That is my secret dream. It sounds horribly whatever, but I would love that.

grace: A little morbid.

padma: A little morbid.

grace: Hey.

padma: I think that is what I would like to happen. Something else, I actually think this is even more important, I would like to make a change. I think with The Bridge Home being a book about hunger and global poverty, but it's also about I would like that to have an impact. I would like readers to not just say, "Oh, that was a great book. I love these characters," close the book and move on. I really hope that they will do something, because hunger is a problem here in our own country. Do something in your neighborhood. Do something somewhere else. I would like my books to cause change in that way, social change.

grace: If your books could cause a social revolution, that would be a pretty awesome thing?

padma: Yeah.

grace: I agree. Thank you very much, Padma.

padma: Thank you so much.