Episode 81! Cleaning Our Mirrors, conversation Anne Nesbet

NOW AVAILABLE TO SUBSCRIBE ON ITUNES

Welcome to episode 81 of our kidlitwomen* podcast! Usually, this podcast features an essay about an issue in the children's literature community (Monday) and a discussion about the essay (Wednesday).

In this episode, Anne Nesbet and Grace Lin discuss Anne’s essay, “Cleaning Our Mirrors,” (which can be heard in episode 80).

Read all the kidlitwomen* essays shared in March

Subscribe to the kidlitwomen* podcast on ITunes

On today's podcast you will hear:

Anne Nesbet writes books for kids and watches a lot of silent films. She lives near San Francisco with her husband, several daughters, and one irrepressible dog. Her books include THE CABINET OF EARTHS, A BOX OF GARGOYLES and THE ORPHAN BAND OF SPRINGDALE as well as Cloud and Wallfish which was recently awarded the California Book Award gold medal in the Juvenile category.

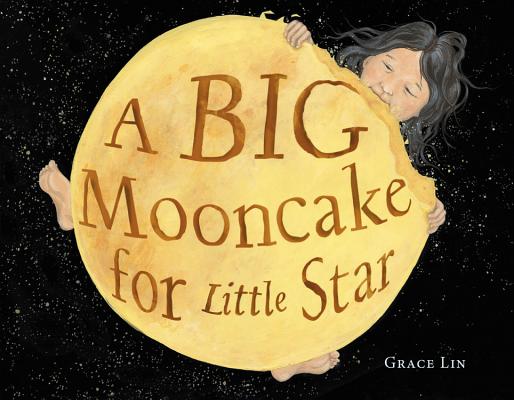

Grace Lin, a NY Times bestselling author/ illustrator, won the Newbery Honor for Where the Mountain Meets the Moon and the Theodor Geisel Honor for Ling and Ting: Not Exactly the Same. Her most recent novel When the Sea Turned to Silver was a National Book Award Finalist and her most recent picture book, A Big Mooncake for Little Star, was awarded the Caldecott Honor. Grace is an occasional commentator for New England Public Radio and video essayist for PBS NewsHour (here & here), as well as the speaker of the popular TEDx talk, The Windows and Mirrors of Your Child’s Bookshelf. She can also be heard on the Book Friends Forever Podcast, with her longtime friend and editor Alvina Ling.

TRANSCRIPT

Grace Lin: Hi everyone, it's Grace Lin, and I'm here talking with Anne Nesbet about her essay, "Cleaning Our Own Mirrors." Hi Anne!

Anne Nesbet: Hi Grace, how are you?

Grace Lin: Good. I'm so glad to talk to you. I thought your essay was really ... it struck a big chord to me. Why don't you tell the listeners about your essay, just in case they missed it or didn't get to hear you read it yet?

Anne Nesbet: Well, my essay was basically inspired by standing in front of a mirror that wasn't clean and remembering suddenly, incredibly vividly, how as children, I was in a family of three girls. We were all trained up to clean mirrors very carefully. There was a certain procedure you had to follow and my mother made sure we all knew how to do it. Then we cleaned the house's mirrors, including the mirror for my father, who was the one person in the household who was not given the mirror cleaning training because at that point in time, that was considered something that girls would do, but a man didn't need to. It seemed to me suddenly that, in many ways, we're all still suffering from using mirrors that are pretty speckled and spackled with old thoughts about what we can and cannot do.

Grace Lin: Well, your essay really struck a nerve with me. My father probably has never cleaned, ever in his life. The joke in my family is that he's called the emperor, so he never does any housework. I just have so many memories when I was reading your essay about how after there was any family gatherings or any parties, it was always all the women and the girls cleaning in the kitchen while the men sat at the dining table or the porch, still talking and laughing.

Anne Nesbet: So true. That was true in my family as well.

Grace Lin: It's kind of this different system of rules that we've let become ingrained in us. How do you feel that affects us as authors?

Anne Nesbet: That's a good question. I think it affects us in many ways and I think the thing about it is that we are never entirely aware of all the ways we're being affected by the strange mirrors we still see ourselves in. It's a constant process of trying to dig through that and figure out what structures of sexism and racism and all the other kinds of weird ideas about ourselves that we get as children are still distorting the way that we see ourselves and see the world and see our place in the world.

Anne Nesbet: As a writer, I think it affects us in a lot of ways. For one thing, the courage to think that you deserve to do the things you care about. That's something that I think is not obvious and something that, especially for women, it's hard to take for granted that you can just boldly go out and say, "Oh, I want to write a book." I mean, that's a leap. It's not necessarily the kind of leap that I was raised to think I should be doing. I think that one of the things that I find, still in myself, is that I like to wait for permission. I like to be invited, rather than to go out and propose myself.

Grace Lin: Yes.

Anne Nesbet: I really don't like to ask for things.

Grace Lin: Yes, I completely agree and I completely empathize with that. Was there anything in your essay that you hesitated about? Was there anything you were afraid maybe people would misunderstand or that you were not sure if you should share?

Anne Nesbet: Well, in a way, I guess the whole thing. I was hesitant also because of my father, who is still alive. I didn't want this to be something that would be hurtful. I think it's ... We're all a part of structures that are larger than ourselves. I am too. We all have to ... There's a certain kind of, I don't know what, it's a mix of courage, but also humility to try to figure out all the ways that we're tangled up in these things that govern the way we think about ourselves.

Grace Lin: Let's talk about the word demanding. That was a really big part of your essay. You asked the readers of your essay to do this experiment where they say a demanding woman versus a demanding man, and what kind of images does that conjure up in your head when you say demanding man versus demanding woman and how does that contrast. How did that experiment work in your head?

Anne Nesbet: I think I was walking to class, I'm a teacher. I think I was walking to class as I was thinking about this, but it occurred to me that demanding is one of those interesting words that can either be rather positive or awfully negative. I was thinking about the ways that we use it. But if you say, for instance, "Oh, that course is a very demanding course. The professor is a demanding professor." Those things actually sound rather good because they're demanding because-

Grace Lin: It sounds like a challenge that you can go for.

Anne Nesbet: Right, exactly. If you can live up to the expectations, then you'll have learned something and moved on. I think the professor in that case is gendered male. I think if you say, "Oh my God, she's so demanding," then for me, instantly I have inner shudder and I'm repelled.

Grace Lin: Yeah, for me, it was really telling because it was all of a sudden I pictured this shrew, the Shakespeare shrew.

Anne Nesbet: Right, exactly.

Grace Lin: Extremely old that you see in olden [inaudible 00:07:11] time plays and pictures. I was like, "Oh, that's terrible."

Anne Nesbet: It's true. It is something that I find very hard in myself, as I was saying, to ask for things because to ask for something feels like it's being demanding. To be demanding, that just goes against everything that I was raised up to believe made a good person. The idea wasn't that you couldn't be successful, but that success had to come to you and you shouldn't be asking for things. If you ask for things or demand them, then even if you get them, they're tainted somehow. It's not pure anymore. I was thinking, "Gosh, that is really messed up because that means it must be a lot harder for us to ask for very basic things like to be treated properly or to be loved or to be paid for our work." In fact, surveys show that that is hard, especially for women.

Grace Lin: I agree. It's not even just the asking for help, it's that we kind of shirk away from being that woman, being that "demanding woman". We don't want to be that. I think about Steve Jobs and they talk about how he was so demanding. They all say that with a lot of admiration. I can't think of anyone using that adjective for a woman and everybody going, "Yeah," with a lot of admiration.

Anne Nesbet: I hope that that's changing. I hope as we get women who are in positions of power and so on, that we could say that without ... Even then, I would say probably it would be an exception for them. It's like the few people whose role outweighs their gender, you know? For the rest of the women, to feel demanding ... For instance, you wouldn't wanna be ... I think sometimes they talk about this on Twitter, like you wouldn't want to be a demanding author or something.

Grace Lin: Yeah.

Anne Nesbet: Again, because writers are largely female, that may be part of the ... You don't want to be seen as demanding by-

Grace Lin: Your editor or your publicist.

Anne Nesbet: Editors, agents, yeah. But then it's hard to sort out, right? What is it reasonable to ask for and what is unreasonable? I think that, in my case, the fear of falling into that demanding category makes me pull the fence very, very close to home about what I think is reasonable to ask for.

Grace Lin: So have you found yourself being more "demanding" since you wrote this essay? Is there anything you'd like to share that you felt, yourself as a person?

Anne Nesbet: That's interesting. I don't know. I'm trying to be, but I don't know. Yes, I think I'm trying to be more open about asking for things. But I think actually, what I'm ... baby steps, in a way, but I'm trying not to punish myself when I do ask for things. So that's step one because I'm the person, I'm like the policeman who is keeping me following these old rules that are the speckled mirror. Of course, that's a shock too. I mean, of course the world also reinforces them, but the person who's doing the best job of making sure that I conform to all of these ideas that I actually don't believe in anymore is my inner self. That's something that, I guess, we all have to wrestle with.

Grace Lin: Yeah. I wanna thank you because of your essay and all of the essays that I read on KidlitWomen, I myself have become more demanding. I'll see somebody speaking at a conference, that's usually a man who's a big keynote speaker. In the past, I'd be like, "Oh, I wish I could get that ... I wish they would ask me." Then I thought about it like, "You know what? I'll ask them." I think it's like, you know what? We have to go for it. I thank you because I think your essay gave me a little bit of a push and courage to, you know what? The worst they can say is no and you have to ask and be demanding. Just be demanding.

Anne Nesbet: Oh, great. So now you've put a huge smile on my face to think that I could be helpful to you because you are just such a role model for somebody who's just does these wonderful, wonderful things in Kidlit.

Grace Lin: Now we have a little love fest.

Anne Nesbet: I'm just so grateful to you, for everything you do.

Grace Lin: So, what do you want people to take away from your essay? If they take anything away from your essay, what's the one thing that you definitely want them to take away?

Anne Nesbet: To think about how our mirrors are distorted by the way that we were raised and the world that we were raised in. Then to think about ways that we can clear some of that distortion from the mirror, and even now, even late in the game, we can become truer people, more authentic people doing a better job of making the world a better place.

Grace Lin: That's great. Awesome. So, we're going to end this conversation with two questions. The first question's very easy. It's just, is there something that you're working on or a book that you'd like to share with our listeners?

Anne Nesbet: Yes, there is. Actually, just a few weeks ago, my new book, The Orphan Band of Springdale came out. It's about a girl named Gusta, who when times get hard, is sent to live in the orphan home run by her grandmother in rural Maine. It happens to be 1941 and that nation is gearing itself up for war and outsiders are met with suspicion. So she has quite a task ahead of herself. Even though she's near-sighted and snaggle toothed and out of place, she has the desire to stand up and do what's right. She has a French horn.

Grace Lin: French horn?

Anne Nesbet: Yeah. So she wants to find a way to make her world a little bit better.

Grace Lin: That sounds great. Do you have a release date for that?

Anne Nesbet: April 10th. It just came out.

Grace Lin: Oh, it just came out. I'm sorry. So say the title again.

Anne Nesbet: It's called The Orphan Band of Springdale.

Grace Lin: Okay. Awesome. Now, my last question. The question that I'm asking everyone is what is your biggest, deepest publishing dream? I'll do the caveat like I always do, that when I ask this question, I want you to think of your biggest dream, your most shallow, most selfish dream, not, "I wanna share my book with the world," because that's what we all want to do. No, I want something that is completely so shallow or so maybe superficial that you're a little bit embarrassed to say it out loud, but you still want it.

Anne Nesbet: It's so funny because when you sent in the email saying, "Oh and I want the large dream. I don't want something little like I want to make a living from writing," and I basically burst into tears from longing, just from that line, making a living from writing. That is a huge dream, but nevermind. If I think about it, what is the dream version of the dream. It is to be able to immerse myself in these other worlds that we create, wholeheartedly. Then to be able to produce worlds through that immersion that make other people want to jump in and immerse themselves into those worlds wholeheartedly. Then send us all back out into the larger world with renewed hearts, in some way. I think that's pretty huge.

Grace Lin: You'd wanna change the world. No, I was hoping you'd do something a little bit more selfish.

Anne Nesbet: Oh, you know that is the most selfish thing I can think of really, is being able to live at once in the real world but also just really live in these worlds that we create when we're creating books. That, for me, that's just the happiest way of living. It is my dream.

Grace Lin: That's awesome. All right, well thank you very much. It was so great talking to you and I loved your essay, so I'm so glad we were able to talk about it today.

Anne Nesbet: Thank you so much, Grace.